Difference between revisions of "Development of retractable foreskin"

WikiModEn2 (talk | contribs) (→Discussion: Improve footnote.) |

WikiModEn2 (talk | contribs) m (→History: Improve footnote) |

||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

|url= | |url= | ||

|quote= | |quote= | ||

| − | |pubmedID= | + | |pubmedID=12765511 |

|pubmedCID= | |pubmedCID= | ||

|DOI= | |DOI= | ||

| − | |date=2003 | + | |date=2003-06-02 |

| − | |accessdate= | + | |accessdate=2019-10-17 |

}}</ref> <ref name="denniston-hill2010">{{REFjournal | }}</ref> <ref name="denniston-hill2010">{{REFjournal | ||

|last=Denniston | |last=Denniston | ||

Revision as of 00:16, 18 October 2019

In the majority of adult men, the foreskin normally retracts to reveal the head of the penis. In newborns, it is common for the foreskin to be fused to the head of the penis by the synechia, thus rendering it non-retractable. The foreskin usually separates from the glans and becomes retractable with age. There is much uncertainty among health care workers about when the foreskin of a boy should become retractable.[1] The mistaken belief that the foreskin was supposed to be retractable at the time of birth of the infant has led to a characterization of the genitalia of most infant males as defective at birth. This has led to many false diagnoses of phimosis, followed by unnecessary circumcision, when, in fact, the foreskin is developmentally normal.

Contents

From a duplicate page

Normally, developmental non-retractability does not cause any problems. Non-retractability may be deemed pathological if it causes problems, such as difficulty urinating or performing normal sexual functions, but even then, this is rare, and, if the non-retractability itself is not caused by pathological inflammation, it cannot be called "pathological" or "true phimosis." A foreskin that is so narrow it will retract very little or not at all, but is not the result of a pathological imflammation, is accurately termed preputial stenosis, and will respond to treatment including steroid creams, manual stretching, and changing masturbation habits.

History

The first data on development of retractile foreskin were provided in 1949 by the famous British paediatrician, Douglas Gairdner.[2] His data have been incorporated into many textbooks and is still being repeated in the medical literature today. Gairdner said that 80 percent of boys should have a retractable foreskin by the age of two years, and 90 percent of boys should have a retractable prepuce by the age of three years.[2]

Unfortunately, Gairdner’s data are inaccurate,[3] [4] [5] so most healthcare providers have been taught inaccurate data.[4] Retractability usually occurs much later than previously believed.[3] This page provides accurate data, derived from newer and better studies, for healthcare providers.

Current view

Almost all boys are born with the foreskin fused with the underlying glans penis. Most also have a narrow foreskin that cannot retract. Non-retractile foreskin is normal at birth and remains common until after puberty (age 18). Some boys develop retractile foreskin earlier, and about 2 percent of males have a non-retractile foreskin throughout life. Non-retractile foreskin is not a disease and does not require treatment.

There are three possible conditions that cause non-retractile foreskin:

- Fusion of the foreskin with the glans penis

- Tightness of the foreskin orifice

- Frenulum breve (which is rare and cannot be diagnosed until the previous two reasons have been eliminated)

The first two reasons are normal in childhood and are not pathological in children. The third can be treated conservatively, retaining the foreskin.

Infants and pre-school

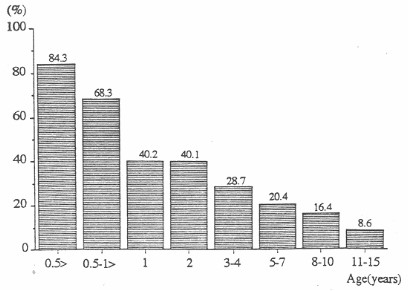

Kayaba et al. (1996) reported that before six months of age, no boy had a retractable prepuce; 16.5 percent of boys aged 3-4 had a fully retractable prepuce.[6] Imamura (1997) examined 4521 infants and young boys. He re-ported that the foreskin is retractile in 3 percent of infants aged one to three months, 19.9 percent of those aged ten to twelve months, and 38.4 percent of three-year-old boys.[7] Ishikawa & Kawakita (2004) reported no retractability at age one, (but increasing to 77 percent at age 11-15).[8] Non-retractile foreskin is the more common condition in this age group. Compare Gairdner’s data.

School-age and adolescence

Jakob Øster, a Danish physician who conducted school examinations, reported his findings on the examination of school-boys in Denmark, where circumcision is rare.[9] Øster (1968) found that the incidence of fusion of the foreskin with the glans penis steadily declines with increasing age and foreskin retractability increases with age.[9] Kayaba et al. (1996) also investigated the development of foreskin retraction in boys from age 0 to age 15.5 Kayaba et al. also reported increasing retractability with increasing age. Kayaba et al. reported that about only 42 percent of boys aged 8-10 have fully retractile foreskin, but the percentage increases to 62.9 percent in boys aged 11-15.5 Imamura (1997) reported that 77 percent of boys aged 11-15 had retractile foreskin.6 Thorvaldsen & Meyhoff (2005) conducted a survey of 4000 young men in Denmark.9 They report that the mean age of first foreskin retraction is 10.4 years in Denmark.[10] Non-retractile foreskin is the more common condition until about 10-11 years of age.

Discussion

Boys usually are born with a non-retractile foreskin. The foreskin gradually becomes retractable over a variable period of time ranging from birth to 18 years or more.[9][10] There is no “right” age for the foreskin to become retractable. Non-retractile foreskin does not threaten health in childhood and no intervention is necessary. Many boys only develop a retractable foreskin after puberty. Education of concerned parents usually is the only action required.[11]

Avoidance of premature retraction

Care-givers and healthcare providers must be careful to avoid premature retraction of the foreskin, which is contrary to medical recommendations, painful, traumatic, tears the attachment points (synechiae), may cause infection, is likely to generate medico-legal problems, and may cause paraphimosis, with the tight foreskin acting like a tourniquet. The first person to retract the boy’s foreskin should be the boy himself.[3] [12]

Making the foreskin retractable

Occasionally a male reaches adulthood with a non-retractile foreskin. Some men with a non-retractile foreskin happily go through life and father children. Other men, however, may want to make their foreskin retractile.

The foreskin can be made retractable by:

Male circumcision is outmoded as a treatment for non-retractile foreskin, but it is still recommended by many urologists because of lack of adequate information, and perhaps because of the profit to the doctor associated with circumcision. Nevertheless, circumcision should be avoided because of pain, trauma, cost,[17][18] complications,[17] difficult recovery, permanent injury to the appearance of the penis, loss of pleasurable erogenous sensation,[19] and impairment of erectile and ejaculatory functions.[20][21]

See also

References

- ↑

Simpson, E.T., Barraclough, P.. The management of the paediatric foreskin. Aust Fam Physician. May 1998; 27(4): 381-383. PMID. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

Simpson, E.T., Barraclough, P.. The management of the paediatric foreskin. Aust Fam Physician. May 1998; 27(4): 381-383. PMID. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ↑ a b

Gairdner, D.. The fate of the foreskin: a study of circumcision. Br Med J. 1949; 2: 1433-7. PMID. PMC. DOI.

Gairdner, D.. The fate of the foreskin: a study of circumcision. Br Med J. 1949; 2: 1433-7. PMID. PMC. DOI.

- ↑ a b c

Wright, J.E.. Further to the "Further Fate of the Foreskin". Med J Aust. 7 February 1994; 160: 134-135. PMID. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

Wright, J.E.. Further to the "Further Fate of the Foreskin". Med J Aust. 7 February 1994; 160: 134-135. PMID. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ↑ a b

Hill, G.. Circumcision for phimosis and other medical indications in Western Australian boys. Med J Aust. 2 June 2003; 178(11): 587. PMID. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

Hill, G.. Circumcision for phimosis and other medical indications in Western Australian boys. Med J Aust. 2 June 2003; 178(11): 587. PMID. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ↑

Denniston, George C., Hill, George. Gairdner was wrong. Can Fam Physician. 1 October 2010; 56(10): 986-7. PMID. PMC. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

Denniston, George C., Hill, George. Gairdner was wrong. Can Fam Physician. 1 October 2010; 56(10): 986-7. PMID. PMC. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ↑

Kayaba, H., Tamura, H., Kitajima, S., et al. Analysis of shape and retractability of the prepuce in 603 Japanese boys. J Urol. 1996; 156(5): 1813-1815.

Kayaba, H., Tamura, H., Kitajima, S., et al. Analysis of shape and retractability of the prepuce in 603 Japanese boys. J Urol. 1996; 156(5): 1813-1815.

- ↑

Imamura, E.. Phimosis of infants and young children in Japan. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1997; 39(3): 403-405.

Imamura, E.. Phimosis of infants and young children in Japan. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1997; 39(3): 403-405.

- ↑

Ishikawa, E., Kawakita, M.. Preputial development in Japanese boys. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2004; 50(5): 305-308.

Ishikawa, E., Kawakita, M.. Preputial development in Japanese boys. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2004; 50(5): 305-308.

- ↑ a b c

Øster, J.. Further fate of the foreskin: incidence of preputial adhesions, phimosis, and smegma among Danish schoolboys. Arch Dis Child. 1968; 43: 200-3. PMID. PMC. DOI. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

Øster, J.. Further fate of the foreskin: incidence of preputial adhesions, phimosis, and smegma among Danish schoolboys. Arch Dis Child. 1968; 43: 200-3. PMID. PMC. DOI. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ↑ a b

Thorvaldsen, M.A., Meyhoff, H.. Patologisk eller fysiologisk fimose? [Pathological or physiological phimosis?] (Danish). Ugeskr Læger. 2005; 167(17): 1858-1862. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

Thorvaldsen, M.A., Meyhoff, H.. Patologisk eller fysiologisk fimose? [Pathological or physiological phimosis?] (Danish). Ugeskr Læger. 2005; 167(17): 1858-1862. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ↑

Spilsbury, K., Semmens, J.B., Wisniewski, Z.S., et al. Circumcision for phimosis and other medical indications in Western Australian boys. Med J Aust. 17 February 2003; 178(4): 155-158. PMID. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

Spilsbury, K., Semmens, J.B., Wisniewski, Z.S., et al. Circumcision for phimosis and other medical indications in Western Australian boys. Med J Aust. 17 February 2003; 178(4): 155-158. PMID. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ↑

(2019).

(2019). Doctors Opposing Forcible Retraction

, Doctors Opposing Forcible retraction. Retrieved 2 October 2019. - ↑

Dunn, H.P.. Non-surgical management of phimosis. Aust N Z J Surg. 1989; 59(12): 963. PMID. DOI.

Dunn, H.P.. Non-surgical management of phimosis. Aust N Z J Surg. 1989; 59(12): 963. PMID. DOI.

- ↑

Beaugé, M.. The causes of adolescent phimosis. Br J Sex Med. 1997; (Sept/Oct): 26.

Beaugé, M.. The causes of adolescent phimosis. Br J Sex Med. 1997; (Sept/Oct): 26.

- ↑

Orsola, A., Caffaratti, J., Garat, J.M.. Conservative treatment of phimosis in children using a topical steroid. Urology. 2000; 56(2): 307-310.

Orsola, A., Caffaratti, J., Garat, J.M.. Conservative treatment of phimosis in children using a topical steroid. Urology. 2000; 56(2): 307-310.

- ↑

Ashfield, J.E., Nickel, K.R., Siemens, D.R., et al. Treatment of phimosis with topical steroids in 194 children. J Urol. 2003; 169(3): 1106-1108.

Ashfield, J.E., Nickel, K.R., Siemens, D.R., et al. Treatment of phimosis with topical steroids in 194 children. J Urol. 2003; 169(3): 1106-1108.

- ↑ a b

Van Howe, RS. Cost-effective treatment of phimosis. Pediatrics. 1998; 102(4): e43. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

Van Howe, RS. Cost-effective treatment of phimosis. Pediatrics. 1998; 102(4): e43. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ↑

Berdeu, D., Sauze, L., Ha-Vinh, P., Blum-Boisgard, C.. Cost-effectiveness analysis of treatments for phimosis: a comparison of surgical and medicinal approaches and their economic effect.. BJU Int. 2001; 87(3): 239-244.

Berdeu, D., Sauze, L., Ha-Vinh, P., Blum-Boisgard, C.. Cost-effectiveness analysis of treatments for phimosis: a comparison of surgical and medicinal approaches and their economic effect.. BJU Int. 2001; 87(3): 239-244.

- ↑

Williams, N., Kapila, L.. Complications of circumcision. Brit J Surg. 1993; 80: 1231-1236. PMID. DOI. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

Williams, N., Kapila, L.. Complications of circumcision. Brit J Surg. 1993; 80: 1231-1236. PMID. DOI. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ↑

Shen, Z., Chen, S., Zhu, C., et al. Erectile function evaluation after adult circumcision. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2004; 10(1): 18-19.

Shen, Z., Chen, S., Zhu, C., et al. Erectile function evaluation after adult circumcision. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 2004; 10(1): 18-19.

- ↑

Masood, S., Patel, H.R.H., Himpson, R.C., et al. Penile sensitivity and sexual satisfaction after circumcision: Are we informing men correctly?. Urol Int. 2005; 75(1): 62-65. PMID. DOI. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

Masood, S., Patel, H.R.H., Himpson, R.C., et al. Penile sensitivity and sexual satisfaction after circumcision: Are we informing men correctly?. Urol Int. 2005; 75(1): 62-65. PMID. DOI. Retrieved 17 October 2019.