Difference between revisions of "Rakai Health Sciences Program"

m |

WikiModEn2 (talk | contribs) (Add two sections.) |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

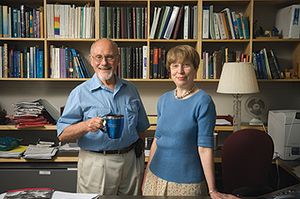

[[Image:Gray and Wawer.jpg|right|thumb|[[Ronald Gray]] & [[Maria Wawer]] (married) head the project.]] | [[Image:Gray and Wawer.jpg|right|thumb|[[Ronald Gray]] & [[Maria Wawer]] (married) head the project.]] | ||

| − | The [[Rakai Health Sciences Program]] (RHSP) is a program that began in 1987 in | + | The [[Rakai Health Sciences Program]] (RHSP) is a program that began in 1987 in Uganda, Africa, to investigate the then-mysterious [[HIV]].<ref name="rakai-history">{{REFweb |

|last=Rakai Project | |last=Rakai Project | ||

|first= | |first= | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

|url=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1mXFdXJaG8k | |url=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1mXFdXJaG8k | ||

|accessdate= | |accessdate= | ||

| − | }}</ref> The RHSP is funded by the [[Johns Hopkins | + | }}</ref> The RHSP is funded by the [[Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School for Public Health]], the Uganda Virus Research Institute, the [[National Institutes of Health]], and the [[Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation]].<ref>{{REFweb |

|last=Rakai Project | |last=Rakai Project | ||

|first= | |first= | ||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

== History of the RHSP == | == History of the RHSP == | ||

| − | The [[Rakai Project]] was created in 1987 by a group of scientists from Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda who decided to investigate HIV infection in the Rakai district by initiating a small community cohort study. The original senior Principal Investigators of the [[Rakai Project]] were Nelson Sewankambo, David Serwadda, and [[Maria Wawer]].<ref name="rakai-history"/> The [[Rakai Project]] has since changed its name to the [[Rakai Health Services Program]], and has a current staff of just under 400 principal investigators, multidisciplinary professionals, and support staff.<ref name="rakai-history"/> | + | The [[Rakai Project]] was created in 1987 by a group of scientists from {{UNI|Makerere University|Mak}} in Kampala, Uganda, who decided to investigate [[HIV]] infection in the Rakai district by initiating a small community cohort study. The original senior Principal Investigators of the [[Rakai Project]] were Nelson Sewankambo, David Serwadda, and [[Maria Wawer]].<ref name="rakai-history"/> The [[Rakai Project]] has since changed its name to the [[Rakai Health Services Program]], and has a current staff of just under 400 principal investigators, multidisciplinary professionals, and support staff.<ref name="rakai-history"/> |

== Promoting circumcision as an HIV prevention method == | == Promoting circumcision as an HIV prevention method == | ||

| − | The RHSP promotes mass circumcision as a means to prevent the spread of HIV. A Youtube video uploaded by the [[ | + | The RHSP promotes mass circumcision as a means to prevent the spread of [[HIV]]. A Youtube video uploaded by the [[Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School for Public Health]] highlights the RHSP's mass circumcision program.<ref name="rakai-jhsph"/> |

{{Citation | {{Citation | ||

| Line 74: | Line 74: | ||

|accessdate= | |accessdate= | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

| − | + | <br><br> | |

<youtube>0rtEdNl322Q</youtube> | <youtube>0rtEdNl322Q</youtube> | ||

| − | + | <br> | |

{{Citation | {{Citation | ||

|Title=Chorus Lyrics | |Title=Chorus Lyrics | ||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

|Source= | |Source= | ||

}} | }} | ||

| + | ==Circumcision does not prevent HIV infection== | ||

| + | === Population-based studies === | ||

| + | {{Population-based studies}} | ||

| + | ===Two African surveys=== | ||

| + | The previously reported studies were from developed Western nations. Now we have information from Sub_Saharan Africa. | ||

| + | |||

| + | French scientist [[Michel Garenne]], Ph.D. has published two reports in 2022 comparing the incidence of HIV infection in [[circumcised]] and [[intact]] men. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In his first report, Garenne presented the findings from a study in Lesotho, the enclave in South Africa. He reported: | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | In couple studies, the effect of circumcision and VMMC on HIV was not significant, with similar transmission from female to male and male to female. The study questions the amount of effort and money spent on VMMC in Lesotho.<ref name="garenne2022A">{{REFjournal | ||

| + | |last=Garenne | ||

| + | |first=Michel | ||

| + | |init=M | ||

| + | |author-link=Michel Garenne | ||

| + | |title=Changing relationships between HIV prevalence and circumcision in Lesotho | ||

| + | |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35373731/ | ||

| + | |date=2022-04-04 | ||

| + | |journal=J Biosoc Sci | ||

| + | |volume=online ahead of print | ||

| + | |pages=1-16 | ||

| + | |DOI=10.1017/S0021932022000153 | ||

| + | |pubmedID=35373731 | ||

| + | |accessdate=2022-11-05 | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In his second report, Garenne (2022) presented information from six Sub-Saharan African nations (Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe). He reported: | ||

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | "Results matched earlier observations made in South Africa that [[circumcised]] and [[intact]] men had similar levels of HIV infection."<ref name="garenne2022B">{{REFjournal | ||

| + | |last=Garenne | ||

| + | |first=Michael | ||

| + | |init=M | ||

| + | |author-link= | ||

| + | |etal=no | ||

| + | |title=Age-incidence and prevalence of HIV among intact and circumcised men: an analysis of PHIA surveys in Southern Africa | ||

| + | |trans-title= | ||

| + | |language= | ||

| + | |journal=J Biosoc Sci | ||

| + | |location= | ||

| + | |date=2022-10-26 | ||

| + | |season= | ||

| + | |volume= | ||

| + | |issue= | ||

| + | |article= | ||

| + | |page= | ||

| + | |pages=1-13 | ||

| + | |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-biosocial-science/article/abs/ageincidence-and-prevalence-of-hiv-among-intact-and-circumcised-men-an-analysis-of-phia-surveys-in-southern-africa/CAA7E7BD5A9844F41C6B7CC3573B9E50 | ||

| + | |archived= | ||

| + | |quote= | ||

| + | |pubmedID=36286328 | ||

| + | |pubmedCID= | ||

| + | |DOI=10.1017/S0021932022000414 | ||

| + | |accessdate=2022-11-05 | ||

| + | }}</ref></blockquote> | ||

| + | {{SEEALSO}} | ||

| + | * [[Circumcision and HIV]] | ||

| + | * [[Foreskin]] | ||

| + | * [[Immunological and protective function of the foreskin]] | ||

| + | * [[Johns Hopkins University]] | ||

{{LINKS}} | {{LINKS}} | ||

| − | * [http://www.jhsph.edu/rakai/ Rakai Health Sciences Program] home page at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School for Public Health | + | * [http://www.jhsph.edu/rakai/ Rakai Health Sciences Program] home page at the [[Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School for Public Health]]. |

| − | |||

{{REF}} | {{REF}} | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Program]] |

[[Category:Circumcision in Africa]] | [[Category:Circumcision in Africa]] | ||

Latest revision as of 00:22, 6 November 2022

The Rakai Health Sciences Program (RHSP) is a program that began in 1987 in Uganda, Africa, to investigate the then-mysterious HIV.[1] The RHSP is headed by husband and wife team Ronald Gray and Maria Wawer (the Senior Principal Investigators),[2] who conduct biased research to look for justifications in rolling out mass circumcision programs around the world.[3] The RHSP is funded by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School for Public Health, the Uganda Virus Research Institute, the National Institutes of Health, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.[4][5]

Contents

History of the RHSP

The Rakai Project was created in 1987 by a group of scientists from Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda, who decided to investigate HIV infection in the Rakai district by initiating a small community cohort study. The original senior Principal Investigators of the Rakai Project were Nelson Sewankambo, David Serwadda, and Maria Wawer.[1] The Rakai Project has since changed its name to the Rakai Health Services Program, and has a current staff of just under 400 principal investigators, multidisciplinary professionals, and support staff.[1]

Promoting circumcision as an HIV prevention method

The RHSP promotes mass circumcision as a means to prevent the spread of HIV. A Youtube video uploaded by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School for Public Health highlights the RHSP's mass circumcision program.[3]

| “ | Rakai Project Doctor Promotes Circumcision It's been hard to change policy because it's a whole new paradigm. We've never used surgery to prevent an infectious disease. Policy makers had to take some time to really wrap their minds around it. – Ronald Gray (Rakai Project)[6] |

Music video

At the Rakai clinic, a propaganda music video promoting circumcision plays continuously in the waiting room.[7][8]

| “ | Chorus Lyrics Men should be circumcised |

| “ | Bridge/Outro Lyrics (female singer) Circumcision has got many benefits. You'll become clean, clean, and cleaner... and when the men are circumcised, it reduces sexual infections in women. Circumcision is SO GOOD. Circumcision is SO SAFE. Men should be circumcised! |

Circumcision does not prevent HIV infection

Population-based studies

September 2021 saw the publication of two huge population studies on the relationship of circumcision and HIV infection:

- Mayan et al. (2021) carried out a massive empirical study of the male population of the province of Ontario, Canada (569,950 males), of whom 203,588 (35.7%) were circumcised between 1991 and 2017. The study concluded that circumcision status is not related to risk of HIV infection.[9]

- Morten Frisch & Jacob Simonsen (2021) carried out a large scale empirical population study in Denmark of 855,654 males regarding the alleged value of male circumcision in preventing HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in men. They found that circumcised men have a higher rate of STI and HIV infection overall than intact men.[10]

No association between lack of circumcision and risk of HIV infection was found by either study. There now is credible evidence that the massive, expensive African circumcision programs have not been effective in preventing HIV infection.

Two African surveys

The previously reported studies were from developed Western nations. Now we have information from Sub_Saharan Africa.

French scientist Michel Garenne, Ph.D. has published two reports in 2022 comparing the incidence of HIV infection in circumcised and intact men.

In his first report, Garenne presented the findings from a study in Lesotho, the enclave in South Africa. He reported:

In couple studies, the effect of circumcision and VMMC on HIV was not significant, with similar transmission from female to male and male to female. The study questions the amount of effort and money spent on VMMC in Lesotho.[11]

In his second report, Garenne (2022) presented information from six Sub-Saharan African nations (Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe). He reported:

"Results matched earlier observations made in South Africa that circumcised and intact men had similar levels of HIV infection."[12]

See also

- Circumcision and HIV

- Foreskin

- Immunological and protective function of the foreskin

- Johns Hopkins University

External links

References

- ↑ a b c

Rakai Project.

Rakai Project. History of the Rakai Health Sciences Program

. Retrieved 2 May 2011. - ↑

Rakai Project.

Rakai Project. Our People at Johns Hopkins University

. Retrieved 2 May 2011. - ↑ a b

JohnsHopkinsSPH (10 January 2012).

JohnsHopkinsSPH (10 January 2012). Rakai Project

. - ↑

Rakai Project.

Rakai Project. Rakai Health Sciences Program

. Retrieved 2 May 2011. - ↑

Kong, Xiangrong (28 February 2011)."18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, Massachusetts". Retrieved 2 May 2011.

Kong, Xiangrong (28 February 2011)."18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, Massachusetts". Retrieved 2 May 2011.

Quote:Longer-term Effects of Male Circumcision on HIV Incidence and Risk Behaviors during Post-trial Surveillance in Rakai, Uganda

Acknowledgements slide Video of Presentation with Slides and Audio Download Link - ↑ JohnsHopkinsSPH. (2010). Rakai Project. YouTube.

- ↑

JohnsHopkinsSPH (10 January 2012).

JohnsHopkinsSPH (10 January 2012). Rakai Project

. - ↑

smugamba (10 October 2006).

smugamba (10 October 2006). Rakai male circumcision video by Stephen Mugamba feat Jemima Sanyu.mpg

. - ↑

Mayan M, Hamilton RJ, Juurlink DN, Austin PC, Jarvi KA. Circumcision and Risk of HIV Among Males From Ontario, Canada. J Urol. 23 September 2021; PMID. DOI. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

Mayan M, Hamilton RJ, Juurlink DN, Austin PC, Jarvi KA. Circumcision and Risk of HIV Among Males From Ontario, Canada. J Urol. 23 September 2021; PMID. DOI. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

Quote:We found that circumcision was not independently associated with the risk of acquiring HIV among men from Ontario, Canada.

- ↑

Frisch M, Simonsen J. Non-therapeutic male circumcision in infancy or childhood and risk of human immunodeficiency virus and other sexually transmitted infections: national cohort study in Denmark. Eur J Epidemiol. 26 September 2021; 37: 251–9. PMID. DOI. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

Frisch M, Simonsen J. Non-therapeutic male circumcision in infancy or childhood and risk of human immunodeficiency virus and other sexually transmitted infections: national cohort study in Denmark. Eur J Epidemiol. 26 September 2021; 37: 251–9. PMID. DOI. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ↑

Garenne M. Changing relationships between HIV prevalence and circumcision in Lesotho. J Biosoc Sci. 4 April 2022; online ahead of print: 1-16. PMID. DOI. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

Garenne M. Changing relationships between HIV prevalence and circumcision in Lesotho. J Biosoc Sci. 4 April 2022; online ahead of print: 1-16. PMID. DOI. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ↑

Garenne M. Age-incidence and prevalence of HIV among intact and circumcised men: an analysis of PHIA surveys in Southern Africa. J Biosoc Sci. 26 October 2022; : 1-13. PMID. DOI. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

Garenne M. Age-incidence and prevalence of HIV among intact and circumcised men: an analysis of PHIA surveys in Southern Africa. J Biosoc Sci. 26 October 2022; : 1-13. PMID. DOI. Retrieved 5 November 2022.