Difference between revisions of "Penis"

WikiModEn2 (talk | contribs) (Move LINKS section.) |

WikiModEn2 (talk | contribs) (→Innervation: relocate citation.) |

||

| Line 139: | Line 139: | ||

== Innervation == | == Innervation == | ||

| − | The penis — the organ of copulation — is heavily innervated with afferent | + | The penis — the organ of copulation — is heavily innervated with afferent<ref>{{REFweb |

|url=https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/afferent | |url=https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/afferent | ||

|title=Afferent | |title=Afferent | ||

| Line 148: | Line 148: | ||

|date=2003 | |date=2003 | ||

|accessdate=2023-11-24 | |accessdate=2023-11-24 | ||

| − | }}</ref> <ref name="cepeda2023">{{REFjournal | + | }}</ref> nerves — meaning that sensation, which is needed for male sexual function, is transmitted to the spinal cord and/or central nervous system,<ref name="cepeda2023">{{REFjournal |

|last=Cepeda-Emiliani | |last=Cepeda-Emiliani | ||

|first= | |first= | ||

Revision as of 11:20, 24 November 2023

The penis is the external male organ of urination and copulation.[1] The penis is also known as the phallus.

The body of the penis consists of three cylindrical-shaped masses of erectile tissue which run the length of the penis. Two of the masses lie alongside each other and end behind the head of the penis. The third mass lies underneath them. This latter mass contains the urethra. The penis terminates in an oval or cone-shaped body, the glans penis, which contains the exterior opening of the urethra.[1]

The glans penis is covered by a loose skin, the foreskin or prepuce, which enables it to expand freely during erection. The skin ends just behind the glans penis and folds forward to cover it, this forming the preputial sac. The inner surface of the foreskin contains glands that secrete a lubricating fluid that mixes with exfoliated tissue to form smegma which makes it easy for the penis to expand and retract past the foreskin.

Contents

Parts

- Root of the penis (radix): It is the attached part, consisting of the bulb of penis in the middle and the crus of penis, one on either side of the bulb. It lies within the superficial perineal pouch.

- Body of the penis (corpus): It has two surfaces: dorsal (posterosuperior in the erect penis), and ventral or urethral (facing downwards and backwards in the flaccid penis). The ventral surface is marked by a groove in a lateral direction.

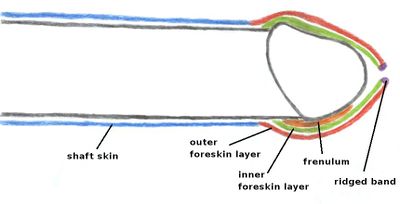

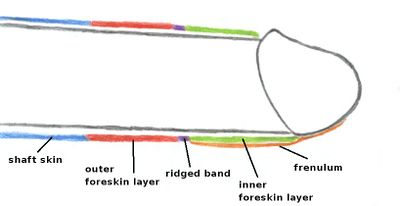

- Epithelium of the penis consists of the shaft skin, the foreskin, and the preputial mucosa on the inside of the foreskin and covering the glans penis. The epithelium is not attached to the underlying shaft so it is free to glide to and fro.[2]

The following content is part of the Circumpendium.

Anatomy and development of the male genital organ

Up to the ninth week of pregnancy, both male and female genital organs develop identically. Genital tubercle, labioscrotal swelling, genital fold and urogenital membrane have developed.

Only after that do the different external features emerge in the fetus. Between the 11th and 17th week the genital tubercle becomes the clitoris in females, and the glans in males.

In girls, the genital fold remains open, in boys it grows together. It transforms into the inner labia and the clitoral hood in girls, and into the foreskin in boys. The labioscrotal swelling becomes the outer labia and scrotum respectively.

The growing together of the folds results in the seam that runs from the underside of the scrotum and the penile shaft up to the tip of the foreskin. The penis now consists of the shaft containing the erectile tissue, with the glans at the top. The shaft is surrounded by the shaft skin which, however, is not knitted to it. This mobility, combined with the stretching capabilities of the skin, allows for the growth in dimension of the penis during an erection. During an erection the erectile tissue fills with blood, giving the penis its stiffness and enlarged size.

In the area of the glans the shaft skin transitions into the outer layer of the foreskin, which extends past the tip of the glans. Parallel to that runs the inner layer of the foreskin. It is attached behind the rim of the glans, and runs between the glans and the outer foreskin layer, also past the tip of the glans. At the tip, the inner and outer foreskin layers are joined together.

This junction makes up the ridged band. At the underside of the penis, in the area of the seam, the inner foreskin layer is connected to the glans by the frenulum.

Like the shaft skin, the foreskin layers are neither fused to the penis, nor to each other, but are moveable against each other. This enables the foreskin to be retracted all the way past the glans until it is stopped by the frenulum.

At the time of birth, the development of the external male genital organs is not completely finished. At this stage, the foreskin and glans share an epithelium (mucous layer, the balano-preputial membrane) that fuses the two together. It serves to protect the glans during infancy, and dissolves as the child develops. Premature forcible retraction of the foreskin will tear this membrane, causing great pain and injury to the boy, who suffers this abuse. The child, himself, should be the first person to retract his foreskin.[3] [4]

Only then the foreskin can be retracted. The age at which this occurs is subject to the child's individual development. If the foreskin is retracted prematurely, before it has fully separated, that can result in painful tears and infections.

The widening of the foreskin also depends on age. A child's foreskin may be too tight to be retracted all the way past the glans, even though it has already completely separated from the glans. This early foreskin tightness, frequently confused with (phimosis), is a normal stage of development and vanishes with increasing age in most boys.

A study by the Danish paediatrician and school doctor, Jakob Øster, of 9,545 examinations of pupils, published in 1968, led to the following results[5]:

| Age | Phimosis | Tightness | Incomplete separation | Not retractable | Fully retractable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 to 7 | 8% | 1% | 63% | 77% | 23% |

| 8 to 9 | 6% | 2% | 58% | 66% | 34% |

| 10 to 11 | 6% | 2% | 48% | 56% | 44% |

| 12 to 13 | 3% | 3% | 34% | 40% | 60% |

| 14 to 15 | 1% | 1% | 13% | 15% | 85% |

| 16 to 17 | 1% | 1% | 3% | 5% | 95% |

Classification according to Øster:

phimosis: Foreskin tightness prohibiting retraction

Tightness: Foreskin tightness hampering retraction

Thorvaldsen & Meyhoff (2005) conducted a survey of 4000 young men in Denmark. They report that the mean age of first foreskin retraction is 10.4 years in Denmark.[6] Non-retractile foreskin is the more common condition until about 10-11 years of age.

Innervation

The penis — the organ of copulation — is heavily innervated with afferent[7] nerves — meaning that sensation, which is needed for male sexual function, is transmitted to the spinal cord and/or central nervous system,[8]

External links

Quartey JKM (2006):

Quartey JKM (2006): Chapter Three

, in: Anatomy and Blood Supply of the Urethra and Penis. Work: Urethral reconstructive surgery. Springer. Pp. 12-17. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

References

- ↑ a b

(2003).

(2003). penis

, The Free Dictionary by Farlex.. Retrieved 23 May 2022. - ↑

Young, Hugh.

Young, Hugh. How the foreskin works

, Circumstitions. Retrieved 2 October 2019. - ↑

Wright JE. Further to the

Wright JE. Further to the Further Fate of the Foreskin

. Med J Aust. 1994; 160: 134-5. PMID. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

Quote:The normal prepuce should be left alone, with no attempt to retract it until the boy is able to do it himself, at the earliest at three years of age.

- ↑

Answers to Your Questions About Premature (Forcible) Retraction of Your Son's Foreskin

Answers to Your Questions About Premature (Forcible) Retraction of Your Son's Foreskin  , NOCIRC (San Anselmo). (2000).

, NOCIRC (San Anselmo). (2000).

- ↑

Øster J. Further Fate of the Foreskin: Incidence of Preputial Adhesions, Phimosis, and Smegma among Danish Schoolboys

Øster J. Further Fate of the Foreskin: Incidence of Preputial Adhesions, Phimosis, and Smegma among Danish Schoolboys  . Arch Dis Child. 1968; 43(228): 200-3. PMID. PMC. DOI. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

. Arch Dis Child. 1968; 43(228): 200-3. PMID. PMC. DOI. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ↑

Thorvaldsen MA, Meyhoff H. Patologisk eller fysiologisk fimose?. Ugeskr Læger. 2005; 167(17): 1858-1862. PMID. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

Thorvaldsen MA, Meyhoff H. Patologisk eller fysiologisk fimose?. Ugeskr Læger. 2005; 167(17): 1858-1862. PMID. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ↑

Anonymous (2003).

Anonymous (2003). Afferent

, The Free Dictionary by Farlex. Retrieved 24 November 2023. - ↑

Cepeda-Emiliani A, Gándara-Cortés M, Otero-Alén M, García H, Suárez-Quintanilla J, García-Caballero T, Gallego R, García-Caballero R. Immunohistological study of the density and distribution of human penile neural tissue: gradient hypothesis. Int J Impot Res. 2 May 2023; 35(3): 286-305. PMID. DOI. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

Cepeda-Emiliani A, Gándara-Cortés M, Otero-Alén M, García H, Suárez-Quintanilla J, García-Caballero T, Gallego R, García-Caballero R. Immunohistological study of the density and distribution of human penile neural tissue: gradient hypothesis. Int J Impot Res. 2 May 2023; 35(3): 286-305. PMID. DOI. Retrieved 24 November 2023.