Difference between revisions of "Intactivism"

WikiModEn2 (talk | contribs) (Add LINKS section.) |

WikiModEn2 (talk | contribs) (→Video: Add video.) |

||

| (30 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | The [[intactivist]] movement (also known as [[genital autonomy]] or [[genital integrity]] movement) is a political movement dedicated to promote the [[genital integrity]] of all people, particularly minors.<ref>{{REFweb | |

| − | + | |url=https://intactamerica.org/intactivism-anti-circumcision/ | |

| − | + | |title=Intactivism 101: An Anti-Circumcision Guide for Foreskin Activism | |

| − | + | |last=Garrett | |

| − | The [[intactivist]] movement (also known as [[genital autonomy]] or [[genital integrity]] movement) is a political movement dedicated to promote the [[genital integrity]] of all people, particularly minors. By “[[genital integrity]],” [[Intactivist|intactivists]] mean the right to grow with intact genitals and to provide informed consent for any genital-altering procedure, with certain exceptions for cases of immediate medical need. Attached to [[genital integrity]] are the concepts of bodily autonomy, informed consent, self determination and the children's right to physical integrity. Intactivists oppose | + | |first=Connor |

| + | |init= | ||

| + | |author-link=Connor Judson Garrett | ||

| + | |publisher=Intact America | ||

| + | |date=2024-02-02 | ||

| + | |accessdate=2024-06-03 | ||

| + | }}</ref> By “[[genital integrity]],” [[Intactivist|intactivists]] mean the right to grow with [[intact]] genitals and to provide [[informed consent]] for any genital-altering procedure, with certain exceptions for cases of immediate medical need. Attached to [[genital integrity]] are the concepts of bodily autonomy, [[informed consent]], self determination and the children's right to [[physical integrity]]. Intactivists oppose non-therapeutic infant [[circumcision]], gender reassignment surgeries for [[intersex]] babies, and [[female genital mutilation]].<ref>{{REFweb | ||

|last=Tennant | |last=Tennant | ||

|first=Sarah | |first=Sarah | ||

| Line 19: | Line 25: | ||

Circumcision of the male, [[infibulation]] of the male [[foreskin]], castration, [[clitoridectomy]], circumcision proper of the female (removal or reduction of the clitoral hood), removal of the nymphae ([[labia minora]]), application of irritants to the genitals, enemas, hysterectomies. The purpose was to reduce excessive sexual desire and its manifestations, such as [[masturbation]], which were suspected to be the cause of many diseases. | Circumcision of the male, [[infibulation]] of the male [[foreskin]], castration, [[clitoridectomy]], circumcision proper of the female (removal or reduction of the clitoral hood), removal of the nymphae ([[labia minora]]), application of irritants to the genitals, enemas, hysterectomies. The purpose was to reduce excessive sexual desire and its manifestations, such as [[masturbation]], which were suspected to be the cause of many diseases. | ||

| − | Before the 19th century, [[circumcision]] existed only as a ritual for some cultures and religions. However, the belief that Jews were immune to [[masturbation]] because of their circumcision, led to the inclusion of circumcision among the plethora of genital surgeries. | + | Before the 19th century, [[circumcision]] existed only as a ritual for some cultures and religions. However, the belief that Jews were immune to [[masturbation]] because of their [[circumcision]], led to the inclusion of [[circumcision]] among the plethora of genital surgeries. |

| − | The late 19th century and early 20th century saw the first opponents of medical circumcision, such as Herbert Snow, Elizabeth | + | The late 19th century and early 20th century saw the first opponents of medical [[circumcision]], such as Herbert Snow, [[Elizabeth Blackwell]], first female {{MD}}<ref>{{REFbook |

|last=Blackwell | |last=Blackwell | ||

|first=Elizabeth | |first=Elizabeth | ||

| Line 32: | Line 38: | ||

|location=London | |location=London | ||

|publisher=J.& A. Churchill | |publisher=J.& A. Churchill | ||

| + | |url=https://archive.org/details/B20442622/page/n9/mode/2up | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

and Ap Morgan Vance, {{MD}}<ref>{{REFbook | and Ap Morgan Vance, {{MD}}<ref>{{REFbook | ||

| Line 49: | Line 56: | ||

|isbn= | |isbn= | ||

|accessdate=2018-11-01 | |accessdate=2018-11-01 | ||

| − | }}</ref>. But by changing the rationale for the procedure, circumcision survived the transformation from the reflex neurosis theory to the germ theory. What started as circumcision of children, became newborn circumcision during and after the World Wars. | + | }}</ref>. But by changing the rationale for the procedure, [[circumcision]] survived the transformation from the reflex neurosis theory to the germ theory. What started as circumcision of children, became newborn [[circumcision]] during and after the World Wars. |

In the [[United Kingdom]], an article by [[Douglas Gairdner]] led the NHS to stop coverage of circumcisions in 1949.<ref>{{REFjournal | In the [[United Kingdom]], an article by [[Douglas Gairdner]] led the NHS to stop coverage of circumcisions in 1949.<ref>{{REFjournal | ||

| Line 64: | Line 71: | ||

|url=http://www.cirp.org/library/general/gairdner/ | |url=http://www.cirp.org/library/general/gairdner/ | ||

|accessdate=2018-11-01 | |accessdate=2018-11-01 | ||

| − | }}</ref>. Ironically, the prevalence of circumcision in the [[United States]] kept growing, with rare opposition. | + | }}</ref>. Ironically, the prevalence of [[circumcision]] in the [[United States]] kept growing, with rare opposition. |

| − | Female genital mutilation never became prevalent, although its practice remained more or less hidden in different places as a punishment for [[masturbation]]. However, since the 1950s, medicine started targeting babies born with atypical genitalia or atypical reproductive organs (intersex) for non-consensual "normalization" surgeries and treatments, some of which have been compared to female genital mutilation. In general, these procedures are now referred to as Intersex Genital Mutilation (IGM) by the intersex community. | + | [[Female genital mutilation]] never became prevalent, although its practice remained more or less hidden in different places as a punishment for [[masturbation]]. However, since the 1950s, medicine started targeting babies born with atypical genitalia or atypical reproductive organs (intersex) for non-consensual "normalization" surgeries and treatments, some of which have been compared to [[female genital mutilation]]. In general, these procedures are now referred to as Intersex Genital Mutilation (IGM) by the [[intersex]] community. |

== Modern intactivism == | == Modern intactivism == | ||

| Line 72: | Line 79: | ||

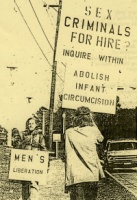

<div style="float:right;">[[File:Van Lewis 1970 CROP.jpg]]</div> | <div style="float:right;">[[File:Van Lewis 1970 CROP.jpg]]</div> | ||

| − | Intactivism as a grassroots movement started in 1970 when [[Van Lewis]] and [[Benjamin Lewis]] protested demanding the abolition of infant circumcision outside a hospital in Tallahassee, Florida. in 1976, [[Jeffrey R. Wood]] established [[INTACT Educational Foundation]] in Wilbraham, Massachusetts. He promoted the adjective “intact” to define the state of the [[penis]] that has its [[foreskin]].<ref>[[Circumcision: The Painful Dilemma]], 1985, p. 346</ref> From a few lone protestors, the movement started becoming organized in the 1980s with the creation of the [[NOCIRC|National Organization of Circumcision Information Resource Centers]] NOCIRC, founded by [[Marilyn Milos]] in 1985, the [[National Organization of Restoring Men]] (NORM), and the [[NOHARMM|National Organization to Halt the Abuse and Routine Mutilation of Males]] (NOHARMM). Non-surgical methods for [[foreskin restoration]] are widely shared. | + | Intactivism as a grassroots movement started in 1970 when [[Van Lewis]] and [[Benjamin Lewis]] protested demanding the abolition of infant [[circumcision]] outside a hospital in Tallahassee, Florida. in 1976, [[Jeffrey R. Wood]] established [[INTACT Educational Foundation]] in Wilbraham, Massachusetts. He promoted the adjective “intact” to define the state of the [[penis]] that has its [[foreskin]].<ref>[[Circumcision: The Painful Dilemma]], 1985, p. 346</ref> From a few lone protestors, the movement started becoming organized in the 1980s with the creation of the [[NOCIRC|National Organization of Circumcision Information Resource Centers]] NOCIRC, founded by [[Marilyn Milos]] in 1985, the [[National Organization of Restoring Men]] (NORM), and the [[NOHARMM|National Organization to Halt the Abuse and Routine Mutilation of Males]] (NOHARMM). Non-surgical methods for [[foreskin restoration]] are widely shared. |

| − | The popularization of internet and the appearance of online social networks contributed to the growth and spread of the intactivist movement during the last decade of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st century.<div style="clear:both;"></div> | + | The popularization of internet and the appearance of online social networks contributed to the growth and spread of the [[intactivist]] movement during the last decade of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st century.<div style="clear:both;"></div> |

== Origin of the name == | == Origin of the name == | ||

| Line 84: | Line 91: | ||

=== Non-therapeutic circumcision of children === | === Non-therapeutic circumcision of children === | ||

| − | Intactivism started specifically as a movement against the non-therapeutic circumcision of male minors. Intactivism does not intend to ban circumcision globally | + | Intactivism started specifically as a movement against the non-therapeutic [[circumcision]] of male minors. Intactivism does not intend to ban circumcision globally — intactivism promotes that all children deserve to grow with [[intact]] genitals, and that genital surgeries — including [[circumcision]] — should only be performed on adults capable of providing [[informed consent]], except in cases of real medical necessity. |

| + | |||

| + | [[Jonathan A. Allan]] quoted [[David Wilton]] who said, "While no gender or person is excluded from those intactivists seek to protect through lobbying and political action, infant boys are the most wide-spread victims of genital cutting in the United States.<ref name="allan2024">{{REFbook | ||

| + | |last=Allan | ||

| + | |first= | ||

| + | |init=JA | ||

| + | |author-link=Jonathan A. Allan | ||

| + | |year=2024 | ||

| + | |title=Uncut: A Cultural Analysis of the Foreskin | ||

| + | |url=https://uofrpress.ca/Books/U/Uncut | ||

| + | |work= | ||

| + | |editor= | ||

| + | |edition= | ||

| + | |volume= | ||

| + | |chapter=Chapter 8: Intactivism and the Logic of Trauma | ||

| + | |page=318 | ||

| + | |location=Regina | ||

| + | |publisher=University of Regina Press | ||

| + | |ISBN= 978-1779400307 | ||

| + | |quote= | ||

| + | |accessdate=2024-12-28 | ||

| + | |note= | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

=== Female genital mutilation === | === Female genital mutilation === | ||

| − | The movement against [[female genital mutilation]] started in the early 20th century in the form of local campaigns in places where the practice is prevalent, such as Kenya, Sudan and Egypt. Feminism took the cause during the 1970s. In 1975 the American social scientist Rose Oldfield Hayes became the first female academic to publish a detailed account of [[FGM]]. Her article in American Ethnologist called it "female genital mutilation," and brought it to wider academic attention. | + | The movement against [[female genital mutilation]] started in the early 20th century in the form of local campaigns in places where the practice is prevalent, such as Kenya, Sudan and Egypt. Feminism took the cause during the 1970s. In 1975 the American social scientist Rose Oldfield Hayes became the first female academic to publish a detailed account of [[FGM]]. Her article in ''American Ethnologist'' called it "[[female genital mutilation]]," and brought it to wider academic attention. |

| − | The [https://www.thegirlgeneration.org/organisations/inter-african-committee-traditional-practices-affecting-health-women-and-children-iac Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children], founded after a seminar in Dakar, Senegal, in 1984, called for an end to the practice, as did the UN's World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna in June 1993. The conference listed FGM as a form of violence against women, marking it as a human-rights violation, rather than a medical issue. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s African governments banned or restricted it. | + | The [https://www.thegirlgeneration.org/organisations/inter-african-committee-traditional-practices-affecting-health-women-and-children-iac Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children], founded after a seminar in Dakar, Senegal, in 1984, called for an end to the practice, as did the UN's World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna in June 1993. The conference listed [[FGM]] as a form of violence against women, marking it as a human-rights violation, rather than a medical issue. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s African governments banned or restricted it. |

| − | The United Nations General Assembly included FGM in resolution 48/104 in December 1993, the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women. In 2003 the UN began sponsoring an International Day of Zero Tolerance to Female Genital Mutilation every February 6. | + | The United Nations General Assembly included [[FGM]] in resolution 48/104 in December 1993, the ''Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women''. In 2003 the UN began sponsoring an International Day of Zero Tolerance to Female Genital Mutilation every February 6. |

| − | In 2008 several United Nations bodies, including the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, published a joint statement recognizing FGM as a human-rights violation.[191] In December 2012 the General Assembly passed resolution 67/146, calling for intensified efforts to eliminate it. | + | In 2008 several United Nations bodies, including the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, published a joint statement recognizing [[FGM]] as a human-rights violation.[191] In December 2012 the General Assembly passed resolution 67/146, calling for intensified efforts to eliminate it. |

| − | Most countries in the world have legislation prohibiting FGM. | + | Most countries in the world have legislation prohibiting [[FGM]]. |

| − | Since | + | Since intactivism is prevalent mostly in countries where [[FGM]] is not prevalent, and since campaigns against FGM are led by recognized global organizations, [[intactivists ]]have very limited action regarding FGM. [[Intactivists]] however remain attentive to ensure that [[FGM]] does not spread to their countries of influence. |

| − | When the [[American Academy of Pediatrics]] in 2010 suggested that "pricking or incising the clitoral [[skin]]" was a harmless procedure that might satisfy parents, intactivist organizations and individuals were quick to respond in condemning the "policy statement on ritual genital cutting of female minors". | + | When the [[American Academy of Pediatrics]] in 2010 suggested that "pricking or incising the clitoral [[skin]]" was a harmless procedure that might satisfy parents, [[intactivist]] organizations and individuals were quick to respond in condemning the "policy statement on ritual genital cutting of female minors". |

| − | While the [[intactivist]] movement at large recognizes all forms of female genital mutilation as harmful, some of the organizations leading the campaigns against FGM do not recognize any harm in male [[circumcision]]. In fact, Catherine Hankins, a circumcision promoter who works for the [[WHO|World Health Organization]], wrote: "it is therefore critical that messaging about male circumcision for [[HIV]] prevention not only clearly distinguishes it from FGM but also contributes to efforts to eradicate FGM". | + | While the [[intactivist]] movement at large recognizes all forms of [[female genital mutilation]] as harmful, some of the organizations leading the campaigns against FGM do not recognize any harm in male [[circumcision]]. In fact, [[Catherine Hankins]], a circumcision promoter who works for the corrupt [[WHO|World Health Organization]], wrote: "it is therefore critical that messaging about male [[circumcision]] for [[HIV]] prevention not only clearly distinguishes it from FGM but also contributes to efforts to eradicate FGM". |

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Campaign_Against_Female_Genital_Mutilation | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Campaign_Against_Female_Genital_Mutilation | ||

=== Intersex surgeries === | === Intersex surgeries === | ||

| − | The history of intersex surgery is intertwined with the development of the specialties of pediatric surgery, pediatric urology, and pediatric endocrinology, with our increasingly refined understanding of sexual differentiation. Ambiguous genitalia has been considered a birth defect throughout recorded history. | + | The history of [[intersex]] surgery is intertwined with the development of the specialties of pediatric surgery, pediatric urology, and pediatric endocrinology, with our increasingly refined understanding of sexual differentiation. Ambiguous genitalia has been considered a birth defect throughout recorded history. |

Genital reconstructive surgery was pioneered between 1930 and 1960 by urologist Hugh Hampton Young and other surgeons at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore and other major university centers. Demand for surgery increased dramatically with better understanding of a condition known as congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and the availability of a new treatment (cortisone) by Lawson Wilkins, Frederick Bartter and others around 1950. | Genital reconstructive surgery was pioneered between 1930 and 1960 by urologist Hugh Hampton Young and other surgeons at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore and other major university centers. Demand for surgery increased dramatically with better understanding of a condition known as congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and the availability of a new treatment (cortisone) by Lawson Wilkins, Frederick Bartter and others around 1950. | ||

| Line 115: | Line 144: | ||

Genital corrective surgeries in infancy were justified by (1) the belief that genital surgery is less emotionally traumatic if performed before the age of long-term memory, (2) the assumption that a firm gender identity would be best supported by genitalia that "looked the part," (3) the preference of parents for an "early fix," and (4) the observation of many surgeons that connective tissue, [[skin]], and organs of infants heal faster, with less scarring than those of adolescents and adults. However, one of the drawbacks of surgery in infancy was that it would be decades before outcomes in terms of adult sexual function and gender identity could be assessed. | Genital corrective surgeries in infancy were justified by (1) the belief that genital surgery is less emotionally traumatic if performed before the age of long-term memory, (2) the assumption that a firm gender identity would be best supported by genitalia that "looked the part," (3) the preference of parents for an "early fix," and (4) the observation of many surgeons that connective tissue, [[skin]], and organs of infants heal faster, with less scarring than those of adolescents and adults. However, one of the drawbacks of surgery in infancy was that it would be decades before outcomes in terms of adult sexual function and gender identity could be assessed. | ||

| − | Intactivism and intersex activism intersected in 1965, when baby [[David Reimer|Bruce Reimer]] had his penis burned during a circumcision. Johns Hopkins psychologist John Money recommended sexually reassigning the baby as a female (conveniently this would serve as an experiment for John Money's theories, as Bruce's twin brother had not been operated). Bruce was renamed Brenda, castrated, subjected to hormone treatment, and raised as a girl. During adolescence, the parents had to tell | + | Intactivism and [[intersex]] activism intersected in 1965, when baby [[David Reimer|Bruce Reimer]] had his [[penis]] burned during a [[circumcision]]. Johns Hopkins psychologist [[John Money]] recommended sexually reassigning the baby as a female (conveniently this would serve as an experiment for John Money's theories, as Bruce's twin brother had not been operated). Bruce was renamed Brenda, castrated, subjected to hormone treatment, and raised as a girl. During adolescence, the parents had to tell him the truth, and Brenda resumed a male identity, now taking the name David. David underwent double mastectomy and two phalloplasties, and replaced hormonal treatment with testosterone. After learning that [[John Money]] continued presenting his case as a success, and that [[intersex]] children were routinely subjected to sexual reassignment, David went public with his story in 1997. David committed [[suicide]] in 2004. |

| − | The 1970s and 1980s were perhaps the decades when surgery and surgery-supported sex reassignment were most uncritically accepted in academic opinion, in most children's hospitals, and by society at large. In this context, enhancing the ability of people born with abnormalities of the genitalia to engage in "normal" heterosexual intercourse as adults assumed increasing importance as a goal of medical management. Many felt that a child could not become a happy adult if his penis was too small to insert in a vagina, or if her vagina was too small to receive a penis. | + | The 1970s and 1980s were perhaps the decades when surgery and surgery-supported sex reassignment were most uncritically accepted in academic opinion, in most children's hospitals, and by society at large. In this context, enhancing the ability of people born with abnormalities of the genitalia to engage in "normal" heterosexual intercourse as adults assumed increasing importance as a goal of medical management. Many felt that a child could not become a happy adult if his [[penis]] was too small to insert in a vagina, or if her [[vagina]] was too small to receive a penis. |

During the 1980s some of these surgeries were discouraged. However, feminizing reconstructive surgery continued to be recommended and performed throughout the 1990s on most virilized infant girls with CAH, as well as infants with ambiguity due to androgen insensitivity syndrome, gonadal dysgenesis, and some XY infants with cloacal exstrophy. | During the 1980s some of these surgeries were discouraged. However, feminizing reconstructive surgery continued to be recommended and performed throughout the 1990s on most virilized infant girls with CAH, as well as infants with ambiguity due to androgen insensitivity syndrome, gonadal dysgenesis, and some XY infants with cloacal exstrophy. | ||

| − | A more abrupt and sweeping re-evaluation of reconstructive genital surgery began about 1997, triggered by a combination of factors. One of the major factors was the rise of patient advocacy groups that expressed dissatisfaction with several aspects of their own past treatments. The Intersex Society of North America was the most influential and persistent, and has advocated postponing genital surgery until a child is old enough to display a clear gender identity and consent to the surgery. [[David Reimer]]'s case became public, destroying the very foundation used to justify early intersex surgeries. | + | A more abrupt and sweeping re-evaluation of reconstructive genital surgery began about 1997, triggered by a combination of factors. One of the major factors was the rise of patient advocacy groups that expressed dissatisfaction with several aspects of their own past treatments. The [[ISNA| Intersex Society of North America]] was the most influential and persistent, and has advocated postponing genital surgery until a child is old enough to display a clear gender identity and consent to the surgery. [[David Reimer]]'s case became public, destroying the very foundation used to justify early [[intersex]] surgeries. |

| − | Numerous organizations have been created to increase public awareness of intersex conditions and advocate for the rights of intersex children to self-determination and [[genital integrity]]. | + | Numerous organizations have been created to increase public awareness of [[intersex]] conditions and advocate for the rights of intersex children to self-determination and [[genital integrity]]. |

| + | |||

| + | In the [[United States]] there are striking parallels between [[intersex]] surgeries and the practice of routine infant [[circumcision]], such as the secrecy of the topics, the rationale for early surgery, and the [[Trauma| physical and psychological effects]] reported by some of the victims. While the organizations generally keep their goals separated, numerous activists are very vocal in both issues. | ||

| − | |||

See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_intersex_surgery | See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_intersex_surgery | ||

| Line 131: | Line 161: | ||

===Intactivism and voluntary genital surgery=== | ===Intactivism and voluntary genital surgery=== | ||

| − | Intactivists do not object to consenting adults undergoing elective genital surgery, although they may question cultural or social influences on the decision (for instance, a man seeking circumcision because his girlfriend finds intact penises “gross”, or labiaplasty influenced by the typical female genitalia presented in pornography). Labiaplasty, sex-change operations, circumcision and other forms of genital modification all come under this category as long as the surgery is entered into freely. | + | Intactivists do not object to consenting adults undergoing elective genital surgery, although they may question cultural or social influences on the decision (for instance, a man seeking [[circumcision]] because his girlfriend finds [[intact]] penises “gross”, or labiaplasty influenced by the typical female genitalia presented in pornography). Labiaplasty, sex-change operations, circumcision and other forms of genital modification all come under this category as long as the surgery is entered into freely, however intactivists are aware of [[regret men]]. |

=== Intactivism and episiotomies === | === Intactivism and episiotomies === | ||

| Line 139: | Line 169: | ||

==Children's right to physical integrity== | ==Children's right to physical integrity== | ||

| − | In 2013, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe presented a resolution promoting the children's right to physical integrity. The resolution stated that "The Parliamentary Assembly is particularly worried about a category of violation of the physical integrity of children, which supporters of the procedures tend to present as beneficial to the children themselves despite clear evidence to the contrary. This includes, among others, female genital mutilation, the circumcision of young boys for religious reasons, early childhood medical interventions in the case of intersex children, and the submission to, or coercion of, children into piercings, tattoos or plastic surgery". | + | In 2013, the Parliamentary Assembly of the [https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/home Council of Europe] presented a resolution promoting the children's right to [[physical integrity]]. The resolution stated that "The Parliamentary Assembly is particularly worried about a category of violation of the physical integrity of children, which supporters of the procedures tend to present as beneficial to the children themselves despite clear evidence to the contrary. This includes, among others, female genital mutilation, the [[circumcision]] of young boys for religious reasons, early childhood medical interventions in the case of [[intersex]] children, and the submission to, or coercion of, children into piercings, tattoos or plastic surgery". |

The resolution recommended that "that member States promote further awareness in their societies of the potential risks that some of the above-mentioned procedures may have on children's physical and mental health, and take legislative and policy measures that help reinforce child protection in this context."<ref name="cepa1952">{{REFdocument | The resolution recommended that "that member States promote further awareness in their societies of the potential risks that some of the above-mentioned procedures may have on children's physical and mental health, and take legislative and policy measures that help reinforce child protection in this context."<ref name="cepa1952">{{REFdocument | ||

| Line 202: | Line 232: | ||

* Educating parents | * Educating parents | ||

| − | == | + | Connor Garrett (2024) suggests numerous ways to support intactivism.<ref name="garrett2024-05-24>{{REFweb |

| + | |url=https://intactamerica.org/ways-to-support-intactivism/ | ||

| + | |title=Championing Change: Effective Ways to Support Intactivism | ||

| + | |last=Garrett | ||

| + | |first=Connor | ||

| + | |init= | ||

| + | |author-link=Connor Judson Garrett | ||

| + | |publisher=Intact America | ||

| + | |date=2024-05-14 | ||

| + | |accessdate=2024-06-13 | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | An anonymous writer has proposed an action plan.<ref>{{REFweb | ||

| + | |url=https://www.reddit.com/user/C4Charkey/comments/1juskx9/the_accidental_intactivist_manifesto_ix/ | ||

| + | |title=The Accidental Intactivist Manifesto: VIII. The Intactivist Uprising: Strategies for a Genital Revolution | ||

| + | |last=C4Charkey | ||

| + | |first= | ||

| + | |init= | ||

| + | |author-link= | ||

| + | |publisher=Reddit | ||

| + | |date=2025-04-08 | ||

| + | |accessdate=2025-04-09 | ||

| + | }}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Video== | ||

| + | ===Early history of intactivism=== | ||

<youtube>o25MjZsmvGY</youtube> | <youtube>o25MjZsmvGY</youtube> | ||

| − | + | ===Doctor explains how intactivism is for everyone=== | |

| + | <youtube>v=JgcYvjboE3Q</youtube> | ||

| + | ===Courageous Conversations: The Fight Against Newborn Genital Mutilation=== | ||

| + | <youtube>v=mZpzr-351M4</youtube> | ||

{{SEEALSO}} | {{SEEALSO}} | ||

* [[Intactivism literature]] | * [[Intactivism literature]] | ||

| + | |||

{{LINKS}} | {{LINKS}} | ||

| − | * http://www.kon.org/urc/v11/wisdom.html | + | * {{REFweb |

| + | |url=https://intactamerica.org/intactivism-anti-circumcision/ | ||

| + | |title=Intactivism 101: An Anti-Circumcision Guide for Foreskin Activism | ||

| + | |last=Garrett | ||

| + | |first=Connor | ||

| + | |init= | ||

| + | |author-link=Connor Judson Garrett | ||

| + | |publisher=Intact America | ||

| + | |date=2024-02-02 | ||

| + | |accessdate=2024-02-17 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | * {{REFweb | ||

| + | |url=https://intactamerica.org/public-opinion-on-circumcision/ | ||

| + | |title=Public Opinion on Circumcision: Can Intactivists Hit A Tipping Point? | ||

| + | |last=Garrett | ||

| + | |first=Connor | ||

| + | |init= | ||

| + | |author-link=Connor Judson Garrett | ||

| + | |publisher=Intact America | ||

| + | |date=2024-03-23 | ||

| + | |accessdate=2024-03-24 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | * {{REFweb | ||

| + | |url=http://www.kon.org/urc/v11/wisdom.html | ||

| + | |title=Advocating Genital Autonomy: Methods of Intactivism in the United States | ||

| + | |last=Wisdom | ||

| + | |first=Travis | ||

| + | |init= | ||

| + | |publisher=Undergraduate Research Journal for the Human Sciences, Volume 11 | ||

| + | |date= | ||

| + | |accessdate=2024-02-17 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | * {{URLwikipedia|http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_intersex_surgery|History of intersex surgery|2024-05-07||EN}} | ||

| + | * {{REFweb | ||

| + | |url=https://www.reddit.com/r/Intactivism/comments/1hr3ifu/revised_debunking_illogical_unethical_reasons/ | ||

| + | |title=Debunking illogical & unethical reasons parents use to justify circumcising their completely healthy sons | ||

| + | |last=Anonymous | ||

| + | |first= | ||

| + | |init= | ||

| + | |publisher=REDDIT | ||

| + | |date=2025-01 | ||

| + | |accessdate=2025-02-15 | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | * {{REFweb | ||

| + | |url=https://www.reddit.com/user/C4Charkey/comments/1jusnxu/the_accidental_intactivist_manifesto_x/ | ||

| + | |title=X. Transcending the Glitch - From Accidental Anthropologist to Intentional Intactivist | ||

| + | |last=C4Charkey | ||

| + | |first= | ||

| + | |init= | ||

| + | |author-link=C4Charkey | ||

| + | |publisher=REDDIT | ||

| + | |date=2025-04-08 | ||

| + | |accessdate=2025-04-13 | ||

| + | }} | ||

{{ABBR}} | {{ABBR}} | ||

{{REF}} | {{REF}} | ||

[[Category:Foreskin restoration]] | [[Category:Foreskin restoration]] | ||

| − | |||

[[Category:Intactivism]] | [[Category:Intactivism]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Intersex]] | ||

[[Category:Term]] | [[Category:Term]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:From IntactWiki]] | ||

[[de:Intaktivismus]] | [[de:Intaktivismus]] | ||

Latest revision as of 18:00, 14 August 2025

The intactivist movement (also known as genital autonomy or genital integrity movement) is a political movement dedicated to promote the genital integrity of all people, particularly minors.[1] By “genital integrity,” intactivists mean the right to grow with intact genitals and to provide informed consent for any genital-altering procedure, with certain exceptions for cases of immediate medical need. Attached to genital integrity are the concepts of bodily autonomy, informed consent, self determination and the children's right to physical integrity. Intactivists oppose non-therapeutic infant circumcision, gender reassignment surgeries for intersex babies, and female genital mutilation.[2]

See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circumcision_controversies#Modern_debates

Contents

Origins

During the late XIX century, in English speaking countries, the theory of irritation and reflex neurosis led to the development of many forms of genital mutilation.[3] Circumcision of the male, infibulation of the male foreskin, castration, clitoridectomy, circumcision proper of the female (removal or reduction of the clitoral hood), removal of the nymphae (labia minora), application of irritants to the genitals, enemas, hysterectomies. The purpose was to reduce excessive sexual desire and its manifestations, such as masturbation, which were suspected to be the cause of many diseases.

Before the 19th century, circumcision existed only as a ritual for some cultures and religions. However, the belief that Jews were immune to masturbation because of their circumcision, led to the inclusion of circumcision among the plethora of genital surgeries.

The late 19th century and early 20th century saw the first opponents of medical circumcision, such as Herbert Snow, Elizabeth Blackwell, first female M.D.[a 1][4] and Ap Morgan Vance, M.D.[a 1][5]. But by changing the rationale for the procedure, circumcision survived the transformation from the reflex neurosis theory to the germ theory. What started as circumcision of children, became newborn circumcision during and after the World Wars.

In the United Kingdom, an article by Douglas Gairdner led the NHS to stop coverage of circumcisions in 1949.[6]. Ironically, the prevalence of circumcision in the United States kept growing, with rare opposition.

Female genital mutilation never became prevalent, although its practice remained more or less hidden in different places as a punishment for masturbation. However, since the 1950s, medicine started targeting babies born with atypical genitalia or atypical reproductive organs (intersex) for non-consensual "normalization" surgeries and treatments, some of which have been compared to female genital mutilation. In general, these procedures are now referred to as Intersex Genital Mutilation (IGM) by the intersex community.

Modern intactivism

Intactivism as a grassroots movement started in 1970 when Van Lewis and Benjamin Lewis protested demanding the abolition of infant circumcision outside a hospital in Tallahassee, Florida. in 1976, Jeffrey R. Wood established INTACT Educational Foundation in Wilbraham, Massachusetts. He promoted the adjective “intact” to define the state of the penis that has its foreskin.[7] From a few lone protestors, the movement started becoming organized in the 1980s with the creation of the National Organization of Circumcision Information Resource Centers NOCIRC, founded by Marilyn Milos in 1985, the National Organization of Restoring Men (NORM), and the National Organization to Halt the Abuse and Routine Mutilation of Males (NOHARMM). Non-surgical methods for foreskin restoration are widely shared.

The popularization of internet and the appearance of online social networks contributed to the growth and spread of the intactivist movement during the last decade of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st century.

Origin of the name

The word intactivism was coined by Richard De Seabra of the National Organization of Restoring Men (NORM) in 1995. It combines the words intact (in reference to intact genitals) and activism.

Areas of interest

Non-therapeutic circumcision of children

Intactivism started specifically as a movement against the non-therapeutic circumcision of male minors. Intactivism does not intend to ban circumcision globally — intactivism promotes that all children deserve to grow with intact genitals, and that genital surgeries — including circumcision — should only be performed on adults capable of providing informed consent, except in cases of real medical necessity.

Jonathan A. Allan quoted David Wilton who said, "While no gender or person is excluded from those intactivists seek to protect through lobbying and political action, infant boys are the most wide-spread victims of genital cutting in the United States.[8]

Female genital mutilation

The movement against female genital mutilation started in the early 20th century in the form of local campaigns in places where the practice is prevalent, such as Kenya, Sudan and Egypt. Feminism took the cause during the 1970s. In 1975 the American social scientist Rose Oldfield Hayes became the first female academic to publish a detailed account of FGM. Her article in American Ethnologist called it "female genital mutilation," and brought it to wider academic attention.

The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children, founded after a seminar in Dakar, Senegal, in 1984, called for an end to the practice, as did the UN's World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna in June 1993. The conference listed FGM as a form of violence against women, marking it as a human-rights violation, rather than a medical issue. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s African governments banned or restricted it.

The United Nations General Assembly included FGM in resolution 48/104 in December 1993, the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women. In 2003 the UN began sponsoring an International Day of Zero Tolerance to Female Genital Mutilation every February 6.

In 2008 several United Nations bodies, including the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, published a joint statement recognizing FGM as a human-rights violation.[191] In December 2012 the General Assembly passed resolution 67/146, calling for intensified efforts to eliminate it.

Most countries in the world have legislation prohibiting FGM.

Since intactivism is prevalent mostly in countries where FGM is not prevalent, and since campaigns against FGM are led by recognized global organizations, intactivists have very limited action regarding FGM. Intactivists however remain attentive to ensure that FGM does not spread to their countries of influence.

When the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2010 suggested that "pricking or incising the clitoral skin" was a harmless procedure that might satisfy parents, intactivist organizations and individuals were quick to respond in condemning the "policy statement on ritual genital cutting of female minors".

While the intactivist movement at large recognizes all forms of female genital mutilation as harmful, some of the organizations leading the campaigns against FGM do not recognize any harm in male circumcision. In fact, Catherine Hankins, a circumcision promoter who works for the corrupt World Health Organization, wrote: "it is therefore critical that messaging about male circumcision for HIV prevention not only clearly distinguishes it from FGM but also contributes to efforts to eradicate FGM".

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Campaign_Against_Female_Genital_Mutilation

Intersex surgeries

The history of intersex surgery is intertwined with the development of the specialties of pediatric surgery, pediatric urology, and pediatric endocrinology, with our increasingly refined understanding of sexual differentiation. Ambiguous genitalia has been considered a birth defect throughout recorded history.

Genital reconstructive surgery was pioneered between 1930 and 1960 by urologist Hugh Hampton Young and other surgeons at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore and other major university centers. Demand for surgery increased dramatically with better understanding of a condition known as congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and the availability of a new treatment (cortisone) by Lawson Wilkins, Frederick Bartter and others around 1950.

Genital reconstructive surgery at that time was primarily performed on older children and adults. In the early 1950s, it consisted primarily of the ability to remove an unwanted or nonfunctional gonad, to bring a testis into a scrotum, to repair a milder chordee or hypospadias, to widen a vaginal opening, and to remove a clitoris.

Genital corrective surgeries in infancy were justified by (1) the belief that genital surgery is less emotionally traumatic if performed before the age of long-term memory, (2) the assumption that a firm gender identity would be best supported by genitalia that "looked the part," (3) the preference of parents for an "early fix," and (4) the observation of many surgeons that connective tissue, skin, and organs of infants heal faster, with less scarring than those of adolescents and adults. However, one of the drawbacks of surgery in infancy was that it would be decades before outcomes in terms of adult sexual function and gender identity could be assessed.

Intactivism and intersex activism intersected in 1965, when baby Bruce Reimer had his penis burned during a circumcision. Johns Hopkins psychologist John Money recommended sexually reassigning the baby as a female (conveniently this would serve as an experiment for John Money's theories, as Bruce's twin brother had not been operated). Bruce was renamed Brenda, castrated, subjected to hormone treatment, and raised as a girl. During adolescence, the parents had to tell him the truth, and Brenda resumed a male identity, now taking the name David. David underwent double mastectomy and two phalloplasties, and replaced hormonal treatment with testosterone. After learning that John Money continued presenting his case as a success, and that intersex children were routinely subjected to sexual reassignment, David went public with his story in 1997. David committed suicide in 2004.

The 1970s and 1980s were perhaps the decades when surgery and surgery-supported sex reassignment were most uncritically accepted in academic opinion, in most children's hospitals, and by society at large. In this context, enhancing the ability of people born with abnormalities of the genitalia to engage in "normal" heterosexual intercourse as adults assumed increasing importance as a goal of medical management. Many felt that a child could not become a happy adult if his penis was too small to insert in a vagina, or if her vagina was too small to receive a penis.

During the 1980s some of these surgeries were discouraged. However, feminizing reconstructive surgery continued to be recommended and performed throughout the 1990s on most virilized infant girls with CAH, as well as infants with ambiguity due to androgen insensitivity syndrome, gonadal dysgenesis, and some XY infants with cloacal exstrophy.

A more abrupt and sweeping re-evaluation of reconstructive genital surgery began about 1997, triggered by a combination of factors. One of the major factors was the rise of patient advocacy groups that expressed dissatisfaction with several aspects of their own past treatments. The Intersex Society of North America was the most influential and persistent, and has advocated postponing genital surgery until a child is old enough to display a clear gender identity and consent to the surgery. David Reimer's case became public, destroying the very foundation used to justify early intersex surgeries.

Numerous organizations have been created to increase public awareness of intersex conditions and advocate for the rights of intersex children to self-determination and genital integrity.

In the United States there are striking parallels between intersex surgeries and the practice of routine infant circumcision, such as the secrecy of the topics, the rationale for early surgery, and the physical and psychological effects reported by some of the victims. While the organizations generally keep their goals separated, numerous activists are very vocal in both issues.

See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_intersex_surgery

Intactivism and voluntary genital surgery

Intactivists do not object to consenting adults undergoing elective genital surgery, although they may question cultural or social influences on the decision (for instance, a man seeking circumcision because his girlfriend finds intact penises “gross”, or labiaplasty influenced by the typical female genitalia presented in pornography). Labiaplasty, sex-change operations, circumcision and other forms of genital modification all come under this category as long as the surgery is entered into freely, however intactivists are aware of regret men.

Intactivism and episiotomies

Many intactivists are also concerned with the process of birth, and consider the routine use of episiotomies by American OB/Gyns, particularly when performed against the wishes of the mother or when consent is obtained by intimidation, as a form of genital mutilation and violence against a mother in a moment of vulnerability.

Children's right to physical integrity

In 2013, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe presented a resolution promoting the children's right to physical integrity. The resolution stated that "The Parliamentary Assembly is particularly worried about a category of violation of the physical integrity of children, which supporters of the procedures tend to present as beneficial to the children themselves despite clear evidence to the contrary. This includes, among others, female genital mutilation, the circumcision of young boys for religious reasons, early childhood medical interventions in the case of intersex children, and the submission to, or coercion of, children into piercings, tattoos or plastic surgery".

The resolution recommended that "that member States promote further awareness in their societies of the potential risks that some of the above-mentioned procedures may have on children's physical and mental health, and take legislative and policy measures that help reinforce child protection in this context."[9]

Testa & Block (2014) considered the child's rights in regard to non-therapeutic male circumcision. They concluded that the circumcision decision should be reserved for the boy to make when he is of age. They concluded:

We claim that libertarianism proscribes the use of violence against innocent people. Babies are innocent; this cannot be denied. Nor will anyone quarrel with the view that circumcision is a violent invasive act, when not undertaken volitionally. Newborns lack the volition to make any such choice for themselves. Hence, it is unjustified, according to libertarian principles. This conclusion does not at all apply to adults who decide to undergo this type of surgery on a voluntary basis. For consenting adults, libertarianism does not at all proscribe circumcision.[10]

Areas of action

- Creating public awareness

- Public protests

- Legislation

- Litigation

- Research

- Educating the medical community

- Educating parents

Connor Garrett (2024) suggests numerous ways to support intactivism.[11]

An anonymous writer has proposed an action plan.[12]

Video

Early history of intactivism

Doctor explains how intactivism is for everyone

Courageous Conversations: The Fight Against Newborn Genital Mutilation

See also

External links

Garrett, Connor (2 February 2024).

Garrett, Connor (2 February 2024). Intactivism 101: An Anti-Circumcision Guide for Foreskin Activism

, Intact America. Retrieved 17 February 2024. Garrett, Connor (23 March 2024).

Garrett, Connor (23 March 2024). Public Opinion on Circumcision: Can Intactivists Hit A Tipping Point?

, Intact America. Retrieved 24 March 2024. Wisdom, Travis.

Wisdom, Travis. Advocating Genital Autonomy: Methods of Intactivism in the United States

, Undergraduate Research Journal for the Human Sciences, Volume 11. Retrieved 17 February 2024. Wikipedia article: History of intersex surgery (EN). Retrieved 7 May 2024.

Wikipedia article: History of intersex surgery (EN). Retrieved 7 May 2024. Anonymous (January 2025).

Anonymous (January 2025). Debunking illogical & unethical reasons parents use to justify circumcising their completely healthy sons

, REDDIT. Retrieved 15 February 2025. C4Charkey (8 April 2025).

C4Charkey (8 April 2025). X. Transcending the Glitch - From Accidental Anthropologist to Intentional Intactivist

, REDDIT. Retrieved 13 April 2025.

Abbreviations

- ↑ a b

Doctor of Medicine

, Wikipedia. Retrieved 14 June 2021. In the United Kingdom, Ireland and some Commonwealth countries, the abbreviation MD is common.

References

- ↑

Garrett, Connor (2 February 2024).

Garrett, Connor (2 February 2024). Intactivism 101: An Anti-Circumcision Guide for Foreskin Activism

, Intact America. Retrieved 3 June 2024. - ↑

Tennant, Sarah (11 December 2009).

Tennant, Sarah (11 December 2009). What is Intactivism?

. Retrieved 23 October 2019. - ↑

Gollaher DL. From ritual to science: the medical transformation of circumcision in America. Journal of Social History. September 1994; 28(1): 5-36. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

Gollaher DL. From ritual to science: the medical transformation of circumcision in America. Journal of Social History. September 1994; 28(1): 5-36. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ↑

Blackwell E (1894): The Human Element in Sex; being a Medical Inquiry into the Relation of Sexual Physiology to Christian Morality. Edition: 2. London: J.& A. Churchill. Pp. 35-36.

Blackwell E (1894): The Human Element in Sex; being a Medical Inquiry into the Relation of Sexual Physiology to Christian Morality. Edition: 2. London: J.& A. Churchill. Pp. 35-36.

- ↑

Vance AM (1900): Surgical Fanaticism. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

Vance AM (1900): Surgical Fanaticism. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ↑

Gairdner D. The fate of the foreskin. Br Med J. 24 December 1949; 2: 1433-1437. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

Gairdner D. The fate of the foreskin. Br Med J. 24 December 1949; 2: 1433-1437. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ↑ Circumcision: The Painful Dilemma, 1985, p. 346

- ↑

Allan JA (2024):

Allan JA (2024): Chapter 8: Intactivism and the Logic of Trauma

, in: Uncut: A Cultural Analysis of the Foreskin. Regina: University of Regina Press. P. 318. ISBN 978-1779400307. Retrieved 28 December 2024. - ↑

Parliamentary Assembly: Children’s right to physical integrity

Parliamentary Assembly: Children’s right to physical integrity  , Contribution:

, Contribution: Resolution 1952

, Council of Europe. (1 October 2013). Retrieved 23 February 2021. - ↑

Testa, Block, Walter E.. Libertarianism and circumcision. Int J Health Policy Manag. May 2014; 3(1): 33-40. PMID. DOI. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

Testa, Block, Walter E.. Libertarianism and circumcision. Int J Health Policy Manag. May 2014; 3(1): 33-40. PMID. DOI. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ↑

Garrett, Connor (14 May 2024).

Garrett, Connor (14 May 2024). Championing Change: Effective Ways to Support Intactivism

, Intact America. Retrieved 13 June 2024. - ↑

C4Charkey (8 April 2025).

C4Charkey (8 April 2025). The Accidental Intactivist Manifesto: VIII. The Intactivist Uprising: Strategies for a Genital Revolution

, Reddit. Retrieved 9 April 2025.