Foreskin restoration

Construction Site

This article is work in progress and not yet part of the free encyclopedia IntactiWiki.

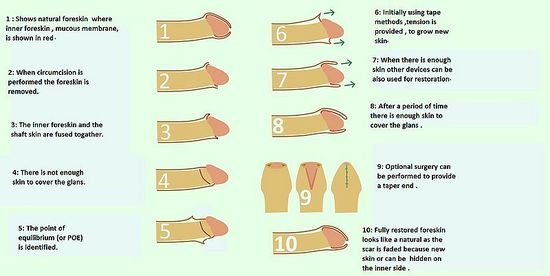

Foreskin restoration refers to the process of expanding the residual skin on the circumcised penis in order to recreate the foreskin which was removed in circumcision. It can also refer to the process of expanding existing skin in a penis whose foreskin is abnormally short or non-existent (see aposthia).

Foreskin restoration can be achieved via surgical and/or non-surgical means. Men take up foreskin restoration to restore sensitivity to the glans penis and to restore the gliding action of the natural penis. Another reason for restoring is a desire to create the natural appearance of an intact penis with the foreskin covering the glans penis. Foreskin restoration techniques are most commonly undertaken by men who resent having been circumcised as children, or who have sustained an injury. They are also used by men who simply desire a longer foreskin.

Contents

History

Foreskin stretching (called "uncircumcision," or epispasm) appears to have been a common practice among Hellenized Jewish men in Hellenistic and Roman societies,[1] from at least as early as the 2nd century BCE.[2]

Key features of Hellenistic culture were athletic exercises in gymnasia and athletic performances in public arenas, where men appeared in the nude. While the penis sheathed in an intact foreskin was normal and acceptable, ancient Greeks and their Hellenistic successors considered the circumcised penis to be offensive, as it was perceived as a vulgar imitation of erection, unfit for public display. The ancient Greeks and their Hellenistic successors considered the "ideal prepuce" to be long, tapered, and "well-proportioned." Removing it was considered mutilation. Men with short foreskins, a condition known as lypodermos, would wear a leather cord called a kynodesme to prevent its accidental exposure.[3]

The sight of circumcised genitals at public baths or gymnasia would inspire laughter and ridicule. Jewish men who wished to gain acceptance in the larger social world gave themselves a presentable appearance by pulling the remaining foreskin forward as far as possible, and keeping it under enough tension to encourage permanent stretching toward its original length. Using a fibular pin or a cord, they pierced the front of the remaining foreskin, drew it forward, and fixed it in place; sometimes they would attach a weight to maintain tension. Over time the foreskin stretched and restored at least some of the appearance of an intact organ.[4] Up until the 2th century, Jewish circumcision involved only partial foreskin removal. Rabbis of the 2th century mandated peri’ah, or the complete ablation of the foreskin in order to prevent Jewish men from engaging in foreskin restoration.[5]

During World War II, some European Jews sought out underground foreskin restoration operations as a way to escape Nazi persecution.[6]

The practice of foreskin restoration was revived in the late twentieth century using modern materials and techniques. In 1982 a group called Brothers United for Future Foreskins (BUFF) was formed, which publicized the use of tape in non-surgical restoration methods. Later in 1991, another group called UNCircumcising Information and Resources Centers (UNCIRC) was formed.[7]

The National Organization of Restoring Men (NORM) was founded in 1989 in San Francisco, as a non-profit support group for men restoring the appearance of a foreskin. It was originally known as RECAP, an acronym for the phrase Recover A Penis. In 1994 UNCIRC was incorporated into this group.[8] Since its founding, several NORM chapters have been founded throughout the United States, as well as internationally in Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and Germany.

Surgical techniques

Surgical methods of foreskin restoration, sometimes known as foreskin reconstruction, usually involve a method of grafting skin onto the distal portion of the penile shaft. The grafted skin is typically taken from the scrotum, which contains the same smooth muscle (known as dartos fascia) as does the skin of the penis. One method involves a four stage procedure in which the shaft is buried in the scrotum for a period of time.[9] Such techniques are costly, and have the potential to produce unsatisfactory results or serious complications related to the skin graft.

British Columbia resident Paul Tinari was held down and circumcised at eight years old, in what he stated was "a routine form of punishment" for masturbation at residential schools. Following a lawsuit, Tinari's surgical foreskin restoration was covered by the British Columbia Ministry of Health. The plastic surgeon who performed the restoration was the first in Canada to have done such an operation, and used a technique similar to that described above.[10][11]

See Surgical foreskin restoration

Nonsurgical techniques

Nonsurgical foreskin restoration is the most commonly used method of foreskin restoration. It is accomplished through tissue expansion and involves pulling on the remnants of the foreskin. Both the skin of the penile shaft and the mucosal inner lining of the foreskin, if any remains after circumcision, may be expanded. The skin is pulled forward over the glans, and tension is applied manually, by using weights or elastic straps. In the latter two cases a device must be attached to the skin; surgical tape is often used.

An example of a device using elastic straps is the T-Tape method, which was developed in the 1990s with the idea of enabling restoration to take place more rapidly. Many specialized restoration devices (like the TLC Tugger shown in the picture) that grip the skin with or without tape are also commercially available. Tension from these devices may be applied by weights or elastic straps, by pushing the skin forward on the penis, or by a combination of these methods.

The amount of tension produced by any method must be adjusted to avoid injury, pain or discomfort, and provides a limit on the rate at which new tissue can be grown. There is a risk of damaging tissues if excessive tension is used, or if tension is applied for too long. Websites about foreskin restoration vary in their recommendations, from suggesting a regimen of moderate amounts of tension applied for several hours a day,[12] to recommending periods of higher tension applied for only a few minutes per day.[13][14]

Applying tension to tissue has long been known to stimulate mitosis, and research shows that regenerated human tissues have the attributes of the original tissue.[15] Unlike conventional skin expansion techniques, however, the process of nonsurgical foreskin restoration may take several years to complete. The time required depends on the amount of skin available to expand, the amount of skin desired in the end, and the regimen of stretching methods used. Patience and dedication are needed; support groups exist to help with these (see External links section). The act of stretching the skin is often described informally as "tugging" in these groups, especially those on the internet.

See Basics of foreskin restoration

Results

Results of surgical foreskin restoration are much faster, but are often described as unsatisfactory, and most restoration groups advise against them.

Results of non-surgical methods vary widely, and depend on such factors as the amount of skin present at the start of the restoration, degree of commitment, technique, and the individual's body. Foreskin restoration successfully restores sensitivity to glans penis and restores the gliding action. Certain parts of the natural foreskin cannot be reformed. In particular, the ridged band, a nerve-bearing tissue structure extending around the penis just inside the tip of the foreskin,[16][17] which helps to contract the tip of the foreskin so that it remains positioned over the glans, cannot be recreated. Restored foreskins can appear much looser at the tip and some men report difficulty in keeping the glans covered. Surgical "touch-up" procedures exist to reduce the orifice of the restored foreskin, recreating the tightening function of the band of muscle fibers near the tip of the foreskin, though they have not proven successful in every case.[18] A loose effect can also be alleviated by creating increased length, but requires a longer commitment to the restoration program. In addition, several websites claim that the use of O-rings during the restoration program can train the skin to maintain a puckered shape.

Regeneration of the foreskin

Recently there has been growing interest in regenerative medicine as a means to regenerate the human male foreskin. This option, unlike foreskin restoration, would result in a true human male foreskin being regrown.

In early 2010, Foregen, a non-profit organization dedicated to funding a clinical trial for the purposes of regrowing the human male foreskin, had been founded. A clinical trial had been scheduled for late 2010, but there were insufficient donations to follow through.[19]

The proposed method would involve placing the patient under general anaesthesia. The penile skin would be opened at the circumcision scar, while the scar tissue is surgically debrided. A biomedical solution would then be applied to both ends of the wound, causing the foreskin to regenerate with the DNA in the patient's own cells. A biodegradable scaffold would be used to offer support for the regenerating foreskin.[20]

Physical aspects

The natural foreskin has three principal components, in addition to blood vessels, nerves and connective tissue: skin, which is exposed exteriorly; mucous membrane, which is the surface in contact with the glans penis when the penis is flaccid; and a band of muscle within the tip of the foreskin. Generally, the skin grows more readily in response to stretching than does the mucous membrane. The ring of muscle which normally holds the foreskin closed is completely removed in the majority of circumcisions and cannot be regrown, so the covering resulting from stretching techniques is usually looser than that of a natural foreskin. According to some observers it is difficult to distinguish a restored foreskin from a natural foreskin because restoration produces a "nearly normal-appearing prepuce."[21]

Nonsurgical foreskin restoration does not restore portions of the frenulum or the ridged band removed during circumcision. Although not commonly performed, there are surgical "touch-up" techniques that can re-create some of the functionality of the frenulum and dartos muscle.[22]

The process of foreskin restoration seeks to regenerate some of the tissue removed by circumcision, as well as providing coverage of the glans. According to research, the foreskin comprises over half of the skin and mucosa of the human penis.[23]

By growing more penile skin, foreskin restorers recover the skin mobility that was eliminated by their circumcision. The ability to glide the skin of the penis over the glans constitutes a mechanical component of the stimulation mechanism of the penis.

In some men, foreskin restoration may alleviate certain problems they attribute to their circumcisions. Such problems, as reported to an anti-circumcision group by men circumcised in infancy or childhood, include prominent scarring (33%), insufficient penile skin for comfortable erection (27%), erectile curvature from uneven skin loss (16%), and pain and bleeding upon erection/manipulation (17%). The poll also asked about awareness of or involvement in foreskin restoration, and included an open comment section. Many respondents and their wives "reported that restoration resolved the unnatural dryness of the circumcised penis, which caused abrasion, pain or bleeding during intercourse, and that restoration offered unique pleasures, which enhanced sexual intimacy."[24]

Some men who have undertaken foreskin restoration report a visibly smoother glans, which some of these men attribute to decreased levels of keratinization following restoration. A study that investigated the effect of glans coverage on levels of keratinisation found no difference in keratin levels[25] within the group studied.

Several studies have suggested that the glans is equally sensitive in circumcised and uncircumcised males,[26][27][28][29] while others have reported that it is more sensitive in uncircumcised males[30][31] (the interpretation of one of these studies is disputed[32]). It has been suggested that the perceived sensitivity gains of the glans reported by some men are psychological, with glans sensitivity itself being unaffected.[33][34]

Emotional, psychological, and psychiatric aspects

Foreskin restoration has been reported as having beneficial emotional results in some men, and has been proposed as a treatment for negative feelings in some adult men about their infant circumcisions.[9][21][35][36]

In "Prepuce Restoration Seekers: Psychiatric Aspects," a 1981 report published in the Archives of Sexual Behavior, four men seeking surgical foreskin restoration were examined. The report provides descriptions of the motivational forces behind the desire for foreskin restoration among these four homosexual men.[37] Schultheiss et al. (1998) are critical of Mohl's report, stating that "loss of prepuce function in sexual activity" is not mentioned, and that in more recent times the majority of the males performing skin-stretching are heterosexual.[38]

Criticism

Kirby states that restoration procedures are "certainly feasible, but they are not without considerable risks, not least of which is loss of sensation of the penile shaft", and comments that "the placebo effect ... cannot be discounted."[39]

It is however naive at best (and malicious at worst) to attribute the satisfaction of foreskin restorers to a placebo effect. A placebo is a simulated or otherwise medically ineffectual treatment. Foreskin restoration grows skin that is as sensitive as the rest of the penile skin, and this provides additional skin mobility (which had been limited by circumcision) and stimulates a physiological change on the surface of the glans. Because foreskin restoration has actual physiological effects, its results cannot be discounted as a simple placebo effect.

Literature

Books, websites and numerous articles have been published about foreskin restoration. See our compiled list of literature about foreskin restoration.

See also

- Basics of foreskin restoration

- Surgical foreskin restoration

- Literature about foreskin restoration

- Foreskin restoration devices

- Films about foreskin restoration

External links

- NORM - National Organization of Restoring Men (U.S.)

- CIRP Foreskin restoration for circumcised males

- NORM-UK - National Organization of Restoring Men (UK)

- My responses to a few Frequently Asked Questions about Non-Surgical Foreskin Restoration, Roy M. Payne; Fryer, Leo (2001-03)

Brandes, S.B.; with McAninch, J.W. [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Surgical methods of restoring the prepuce: a critical review. [[Journal|BJU International]]. 1999; 83(Suppl. 1): 109-13. DOI.

Brandes, S.B.; with McAninch, J.W. [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Surgical methods of restoring the prepuce: a critical review. [[Journal|BJU International]]. 1999; 83(Suppl. 1): 109-13. DOI.

References

- ↑

Rubin, Jody P.. Celsus's Decircumcision Operation. Urology. July 1980; 16(1): 121-4. PMID. DOI.

Rubin, Jody P.. Celsus's Decircumcision Operation. Urology. July 1980; 16(1): 121-4. PMID. DOI.

- ↑

Glick, Leonard (2005):

Glick, Leonard (2005): "This Is My Covenant", Circumcision in the World of Temple Judaism

, in: Marked in Your Flesh. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 31. ISBN 0-19-517674-X. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

Quote:Foreskin stretching (called "uncircumcision," or epispasm) appears to have been a common practice among Hellenized Jewish men...

- ↑ Hodges FM. [http://www.cirp.org/library/history/hodges2/ Hodges, Frederick M. The Ideal Prepuce in Ancient Greece and Rome: Male Genital Aesthetics and Their Relation to Lipodermos, Circumcision, Foreskin Restoration, and the Kynodesme. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, vol. 75, no. 3 (Fall 2001): pp. 375-405.

- ↑

Glick, Leonard (2005):

Glick, Leonard (2005): "This Is My Covenant", Circumcision in the World of Temple Judaism

, in: Marked in Your Flesh. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 31. ISBN 0-19-517674-X. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

Quote:...some, eager for acceptance in the larger social world, gave themselves a presentable appearance by pulling the remaining foreskin forward...

- ↑

Glick, Leonard (2005):

Glick, Leonard (2005): "This Is My Covenant", Circumcision in the World of Temple Judaism

, in: Marked in Your Flesh. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 31. ISBN 0-19-517674-X. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

Quote:For obvious reasons this was anathema to the rabbis: tantamount to rejection of Judaism and defiance of rabbinic authority.

- ↑

Tushmet, Leonard. Uncircumcision. Medical Times. 1965; 93(6): 588-93.

Tushmet, Leonard. Uncircumcision. Medical Times. 1965; 93(6): 588-93.

- ↑

Bigelow, Jim. Uncircumcising: undoing the effects of an ancient practice in a modern world. Mothering. 1994; Summer: 121–4.

Bigelow, Jim. Uncircumcising: undoing the effects of an ancient practice in a modern world. Mothering. 1994; Summer: 121–4.

- ↑

Griffiths, R. Wayne.

Griffiths, R. Wayne. NORM - History

. Retrieved 21 August 2006. - ↑ a b

Greer, Donald M.; with Mohl, Paul C.; Sheley, Kathy A. [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. A technique for foreskin reconstruction and some preliminary results. The Journal of Sex Research. 1982; 18(4): 324-30. DOI.

Greer, Donald M.; with Mohl, Paul C.; Sheley, Kathy A. [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. A technique for foreskin reconstruction and some preliminary results. The Journal of Sex Research. 1982; 18(4): 324-30. DOI.

- ↑

Euringer, Amanda. BC Health Pays to Restore Man's Foreskin. The Tyee. 25 July 2006;

Euringer, Amanda. BC Health Pays to Restore Man's Foreskin. The Tyee. 25 July 2006;

- ↑

Laliberté, Jennifer. BC man's foreskin op a success. National Review of Medicine. 30 June 2006; 3(12)

Laliberté, Jennifer. BC man's foreskin op a success. National Review of Medicine. 30 June 2006; 3(12)

- ↑

Griffiths, R. Wayne.

Griffiths, R. Wayne. NORM - Recommended Restoration Regimen

. Retrieved 27 August 2006. - ↑

Foreskin Restoration Chat Manual Restoration Method and Guide

. Retrieved 27 August 2006. - ↑

Manual Methods of Foreskin Restoration

. Retrieved 19 July 2007. - ↑

Cordes, Stephanie; with Calhoun, Karen H.; Quinn, Francis B. [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Tissue Expanders. University of Texas Medical Branch Department of Otolaryngology Grand Rounds. 15 October 1997;

Cordes, Stephanie; with Calhoun, Karen H.; Quinn, Francis B. [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Tissue Expanders. University of Texas Medical Branch Department of Otolaryngology Grand Rounds. 15 October 1997;

- ↑

Taylor, John R. (4 February 1997).

Taylor, John R. (4 February 1997). Interview with John Taylor

. Retrieved 26 August 2007. - ↑

Bigelow: The Joy of Uncircumcising!. Pp. 13. ISBN 096304821X.

Bigelow: The Joy of Uncircumcising!. Pp. 13. ISBN 096304821X.

- ↑

Bigelow: The Joy of Uncircumcising!. Edition: 1998. Pp. 188–192. ISBN 096304821X.

Bigelow: The Joy of Uncircumcising!. Edition: 1998. Pp. 188–192. ISBN 096304821X.

- ↑

Foregen 21 September 2010; Retrieved 28 November 2010.

Foregen 21 September 2010; Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ↑

Clinical Regen Trial error; Retrieved 23 June 2010.

Clinical Regen Trial error; Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ↑ a b

Goodwin, Willard E.. Uncircumcision: A Technique For Plastic Reconstruction of a Prepuce After Circumcision. Journal of Urology. 1990; 144(5): 1203-5. PMID.

Goodwin, Willard E.. Uncircumcision: A Technique For Plastic Reconstruction of a Prepuce After Circumcision. Journal of Urology. 1990; 144(5): 1203-5. PMID.

- ↑ Bigelow, Jim. The Joy of Uncircumcising!, pp. 188-191.

- ↑ Taylor JR, Lockwood AP, Taylor AJ.

The prepuce: Specialized mucosa of the penis and its loss to circumcision

. Br J Urol 1996;77:291-295. - ↑

Hammond, T.. A Preliminary Poll of Men Circumcised in Infancy or Childhood. BJU International. 1999; 83(Suppl. 1): 85-92. PMID. DOI.

Hammond, T.. A Preliminary Poll of Men Circumcised in Infancy or Childhood. BJU International. 1999; 83(Suppl. 1): 85-92. PMID. DOI.

- ↑

How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection?

. - ↑

William H. Masters; Virginia E. Johnson (1966): Human Sexual Response. Boston: Little, Brown & Co. Pp. 189–91. ISBN 0-316-54987-8. (excerpt accessible here)

William H. Masters; Virginia E. Johnson (1966): Human Sexual Response. Boston: Little, Brown & Co. Pp. 189–91. ISBN 0-316-54987-8. (excerpt accessible here)

- ↑

Bleustein, Clifford B.; with James D. Fogarty, Haftan Eckholdt, Joseph C. Arezzo and Arnold Melman [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Effect of neonatal circumcision on penile neurologic sensation. Urology. 1 April 2005; 65(4): 773-7. PMID. DOI.

Bleustein, Clifford B.; with James D. Fogarty, Haftan Eckholdt, Joseph C. Arezzo and Arnold Melman [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Effect of neonatal circumcision on penile neurologic sensation. Urology. 1 April 2005; 65(4): 773-7. PMID. DOI.

- ↑

Bleustein, Clifford B., with: Haftan Eckholdt, Joseph C. Arezzo and Arnold Melman: American Urological Association 98th Annual Meeting, Chicago, Illinois. (error) Effects of Circumcision on Male Penile Sensitivity.

Bleustein, Clifford B., with: Haftan Eckholdt, Joseph C. Arezzo and Arnold Melman: American Urological Association 98th Annual Meeting, Chicago, Illinois. (error) Effects of Circumcision on Male Penile Sensitivity.

- ↑

Payne, Kimberley; with Thaler, Lea; Kukkonen, Tuuli; Carrier, Serge; and Binik, Yitzchak [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Sensation and Sexual Arousal in Circumcised and Uncircumcised Men. Journal of sexual medicine. May 2007; 4(3): 667-674. DOI.

Payne, Kimberley; with Thaler, Lea; Kukkonen, Tuuli; Carrier, Serge; and Binik, Yitzchak [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Sensation and Sexual Arousal in Circumcised and Uncircumcised Men. Journal of sexual medicine. May 2007; 4(3): 667-674. DOI.

- ↑

Sorrells. Fine-touch pressure thresholds in the adult penis. British Journal of Urology International. 1 April 2007; 99(4): 864-869.

Sorrells. Fine-touch pressure thresholds in the adult penis. British Journal of Urology International. 1 April 2007; 99(4): 864-869.

- ↑

Yang, DM; with Lin H, Zhang B, Guo W [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Circumcision affects glans penis vibration perception threshold. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 1 April 2008; 14(4): 328-330. PMID.

Yang, DM; with Lin H, Zhang B, Guo W [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Circumcision affects glans penis vibration perception threshold. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue. 1 April 2008; 14(4): 328-330. PMID.

- ↑

Waskett, Jake H.; with Brian J. Morris [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Fine touch pressure thresholds in the adult penis. BJU International. May 2007; 99(6): 1551-1552. PMID. DOI.

Waskett, Jake H.; with Brian J. Morris [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Fine touch pressure thresholds in the adult penis. BJU International. May 2007; 99(6): 1551-1552. PMID. DOI.

- ↑

The Joy of Uncircumcising! Restore Your Birthright and Maximize Sexual Pleasure

. - ↑

Circumcision and uncircumcision

. - ↑

Penn, Jack. Penile Reform. British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 1963; 16(287-8) PMID. DOI.

Penn, Jack. Penile Reform. British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 1963; 16(287-8) PMID. DOI.

- ↑

Boyle, GJ; with Goldman R.; Svoboda, J.S.; Fernandez, E. [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Male Circumcision: Pain, Trauma and Psychosexual Sequelae. Journal of Health Psychology. 2002; 7(3): 329-43. DOI.

Boyle, GJ; with Goldman R.; Svoboda, J.S.; Fernandez, E. [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Male Circumcision: Pain, Trauma and Psychosexual Sequelae. Journal of Health Psychology. 2002; 7(3): 329-43. DOI.

- ↑

Mohl, PC; with Adams R, Greer DM, Sheley KA [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Prepuce restoration seekers: psychiatric aspects. [[Journal|Archives of Sexual Behavior]]. 1982; 10(4): 383-93. PMID. DOI.

Mohl, PC; with Adams R, Greer DM, Sheley KA [deprecated REFjournal parameter used: <coauthors> - please use <last2>, etc.]. Prepuce restoration seekers: psychiatric aspects. [[Journal|Archives of Sexual Behavior]]. 1982; 10(4): 383-93. PMID. DOI.

- ↑ Schultheiss D, Truss MC, Stief CG, Jonas U. Uncircumcision: a historical review of preputial restoration. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;101(7): 1990-8.

- ↑

Kirby, RS. Views and reviews: The Joy of Uncircumcising! Restore Your Birthright and Maximize Sexual Pleasure. BMJ. 1994; 309(6955): 679.

Kirby, RS. Views and reviews: The Joy of Uncircumcising! Restore Your Birthright and Maximize Sexual Pleasure. BMJ. 1994; 309(6955): 679.